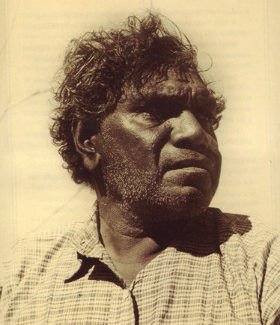

ALBERT NAMATJIRA

BIOGRAPHY

Often portrayed as a tragic figure, Albert Namatjira was the first Aboriginal artist to be recognised internationally, having made a lasting contribution to Australian art through romantic depictions of the desert that have become synonymous with our vision of the Australian outback.

Following an exhibition of paintings by a small group of European artists led by Rex Battarbee in the Hermannsburg community in 1934, Albert approached the mission superintendent for help in obtaining paint and paper. These were set aside for him until Battarbee returned to the community in 1936. He pleaded to be taken on as a camel man for the painting trip that year and during the subsequent months demonstrated a natural gift for painting. The expedition proved to be an exchange in which, in return for Albert’s guiding expertise Battarbee taught him his method of landscape watercolour painting. Albert’s skill so impressed Batarbee that he noted after only a brief period 'I felt he had done so well that he had no more to learn from me about colour' (Morphy 1998: 268).

Namatjira’s aptitude in capturing the high colouring of the desert landscape, the gorges and valleys of the country of his birth and his Dreaming, brought him instant success. At his first exhibition in Melbourne during 1938 all 41 watercolours sold within a few days. Prior to this exhibition he had simply signed his works ‘Albert’ but added his father’s tribal name after that time. This was followed by another highly successful exhibition in Adelaide during which 20 paintings sold in the first half hour, and the Art Gallery of South Australia purchased a major work, the first of his paintings to be purchased by an Australian public gallery. By this time Albert had already become one of Australia’s best-known artists. Indeed Alison French, curator of his 2002 National Gallery of Australia retrospective, relates how, in 1951, a small blue envelope reached the post office in Alice Springs addressed simply to ‘Albert Namatjira. Famous Aboriginal Artist. Australia.’ It had been posted in India by an autograph hunter.

Namatjira painted almost all of his paintings during the winter months and they were almost all landscapes. He did, however, paint the occasional work with groups of figures. During the Second World War he began to sell paintings directly to collectors for between one and five guineas each. Soon he had so many orders that it was decided that an Advisory Council should be established to supervise both the standard and sale of his works. Albert was told to restrict himself to just 50 works per year, and that his prices should be fixed between three and 15 guineas. However, his next show in Melbourne was another great success with works selling for up to 35 guineas. In 1945, a successful exhibition netted 1,000 guineas and allowed him to build his cottage a few kilometres from Hermannsburg.

Following this success, he took a number of other Aranda artists including his sons Enos and Oscar and the three Pareroultja brothers on his painting expeditions with him. They spawned a movement of naturalistic watercolours in the European tradition of classical landscape painting. The movement termed the Hermannsburg school, the name of the Lutheran church mission station where Albert was born, was the first significant transitional art movement to emerge from Aboriginal Australia. By this time Albert already had ten children. In 1946 he received a visit from His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester, then Governor General of Australia, and a work was presented to Princess Elizabeth on her 21st birthday. Other successful shows followed and Charles Mountford and Axel Poignant made the film Namatjira, the Painter in 1948.

However, his adaptation of a European medium brought with it a bitter twist. Albert’s 'paintings were undoubtedly appreciated because of their aesthetic appeal, but they were at the same time a curiosity and a sign that Aborigines could be civilised' (Morphy 1998: 270). In an era of cultural assimilation, his ability to paint as a white man gave proof 'that Aboriginals would eventually merge into white society and loose their cultural identity' (Beier 1986: 32). Thus Geoff Bardon wrote 'eulogies focused on the miraculous fact of his aboriginality, never just his art' (1989: 19). Indeed, Namatjira was awarded citizenship by the Australian government, an awkward symbol that his adoption of European traditions elevated his status as a human being. Ironically he became the first Aboriginal to be listed in Who’s Who in Australia.

His perceived 'assimilation' would later bring his work in to disrepute. It became seen as a symbol of subordination, most especially after 'a group of Aboriginal artists from Papunya quietly carried out a cultural revolution that would totally debunk the theory of assimilation,' during the 1970's. They clearly demonstrated the possibility that Aboriginal culture could interact with the modern world, without compromising its own artistic traditions (Beier 1986: 34). It has only been with hindsight that Namatjira’s work has undergone a reassessment. In more recent times his work has been cited as 'evidence of a tradition of resistance that represented an Aboriginal perspective on the landscape of central Australia, albeit through a European medium' (Morphy 1998: 265). Regardless of how acutely Albert intended his works to resist assimilation, what was restored in this reappraisal was a recognition that his work portrayed his traditional connection to his land. Namatjira’s style, upon reconsideration is distinctly his own.

Interestingly Namatjira painted most of his desert country from a slightly elevated point of view, as if looking down, ever so slightly on the landscape. He was able to capture the subtleties of colour as the desert changes from the soft tones of summer heat, to the rich colours of the early morning and late evening light. The majority of his paintings lack a central focal point yet,'a visual emphasis on the edges holds the composition in balance without either a dominance of forms near the centre or a hierarchy of forms’ (Morphy 1998: 273).

Unfortunately human life is often more vulnerable than the pendulum of social acceptance and opinion. Namatjira passed away in tragic circumstances in 1959, after being jailed for bringing alcohol into his community. Cruelly, though his citizenship gave him the right to buy alcohol, it did not permit him to share it with other members of the community. While Albert Namatjira is 'often characterized as a tragic figure trapped between two worlds and two art traditions' (Bardon 1989: 18) his paintings of the Western MacDonnell Ranges, Mount Sonder and the surrounding desert have endured to become synonymous with a romantic vision of the Australian outback. His paintings have 'opened our eyes and our senses to new ways of seeing the centre' (French 2002: 1), forever usurping the sightless colonial appraisal of the desert as a barren wasteland.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Bardon, G. 1989. Mythscapes: Aboriginal Art of the Desert. Ryan, J (ed). National Gallery of Victoria.

Beier, U. August 1986. ‘Papunya Tula Art: The End of Assimilation.’ Aspect Vol. 34: 32-37.

French, A. 2002. Seeing the Centre: The Art of Albert Namatjira 1902-1959. National Gallery of Australia.

McKenzie A, Albert Namatjira 1902-1959, Famous Australian Art Series, Oz Publishing Co. 1988, Brisbane

Morphy, H. 1998. Aboriginal Art. Phaidon Press.

West, M.K.C., (ed.), 1988, The Inspired Dream, Life as art in Aboriginal Australia, exhib. cat., Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.