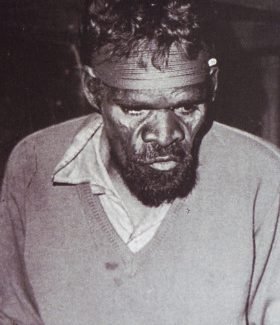

ANATJARI NO. I TJAKAMARRA

BIOGRAPHY

Antajari was one of the last group of desert nomads to leave his homeland and settle at Papunya.* From the outset he emerged as a focused and compelling artistic presence within the initial painting group. Geoff Bardon remembered him as 'a slightly built man with a particularly calm and gentle manner…very attentive and interested in what was going on but saying nothing' (2004: 71).

When he began painting he was working with Uta Uta as a gardener at the local school. He used to congregated after work with others in the small flat where the first discussions and artistic experiments began. Soon, a separate painting area was established and the different tribes with their specific Dreamings, often connected through a once shared terrain, came together as one painting group. 'They were extraordinarily happy to have an opportunity to paint their own stories,' Bardon later wrote, 'At least five or six separate groups of men joined in the sudden blossoming of their traditional art, each in their own way…accompanied by friends who also wanted to draw, paint or sell something' (1986: 39). Bardon played a crucial role as friend and adviser in guiding the raw intensity of early experimentation towards a more disciplined and workable visual language. Within the medley of early free form, some of the men responded more acutely to his explanations of stylistic intelligibility and the dynamics of pattern and form, despite language difficulties and conceptual differences. Anatjari, worked with concentrated attention, always in his customary spot, rarely speaking, refining his method and helping to forge the distinctive Pintupi style. Anatjari’s early works were influenced strongly by the precise line work of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, which in time came to characterise his own paintings. These were noted by Dick Kimber to be ritually very correct and to contain secret imagery meant only for the eyes of initiated men

Anatjarri's finely crafted compositions were informed by his deep wish and need to reconnect with his country and the sacred sites that gave life and meaning to his people. Their 'highly accessible visual logic' stemmed from his ability to pare down significant features of a Dreaming ceremony or journey into a well-balanced and synchronized whole (Sutton 1988: 81). In building on the arrangement of geometric forms, and reflecting their earthbound origins through traditional colours, Anatjari’s strong use of line emitted a powerful sense of gravitas. He was, as Bardon explained, 'forever traveling west to his beloved homelands and affirming the sacredness of the places there' (2004: 50). By thinning the consistency of his paint he created a slightly translucent effect, imparting a distinctive quality that has been attributed to a constant and close reading of the land as a blueprint for nomadic survival and spiritual sustenance. The graphic network, of lines of travel, linking sites or resting places, forms a dense map of Pintupi country. The Tingari Cycle, Anatjari’s enduring subject, re-traces and re-affirms this relationship between the land, its people and their mythology.

Supported by his artistic success Anatjari was able to return to his homelands in the early 1980’s. He played a leading role in the establishment of Tjukurla outstation, situated between Kintore and Docker River and lived there for a number of years. From here he painted works which were included in the landmark exhibitions Dot and Circle 1985, Face of the Centre, National Gallery of Victoria 1985, Dreamings The Art of Aboriginal Australia, Asia Society New York 1988 and The Inspired Dream which toured nationally and internationally throughout 1988. He lived and worked at the new settlement of Kiwirrkurra through the mid to late 1980’s and, prior to his death in 1992, had solo exhibitions at John Weber Gallery in New York and Gabrielle Pizzi Gallery in Melbourne. Anatjari No. III Tjakamarra was by this time represented in many international collections and honoured as one of the masters of the earliest period of contemporary Aboriginal desert art. Having lived beyond the regular reach of Papunya Tula for a large part of his later life he became one of the first Pintupi artists to work independently of the company. He was the first of the Western Desert painters to be represented in a major international art collection when his work was selected from the Papunya Tula exhibition at John Weber Gallery in 1988 for inclusion in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Subject of the book The Lizard Eaters by Douglas Woodlock and the documentary film Desert People by Ian Dunlop.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya; A Place Made After the Story, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2004.

Bardon, Geoff, “The Origins of the Painting Movement” in Dot and Circle; a retrospective survey of the Aboriginal acrylic paintings of Central Australia, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 1986.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Ryan, J., 1989, Mythscapes Aboriginal Art of the Desert from the National Gallery of Victoria, exhib. cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Sutton, Peter, “The Morphology of Feeling” in Dreamings; The Art of Aboriginal Australia, edited by Peter Sutton, Penguin, Australia, 1988.