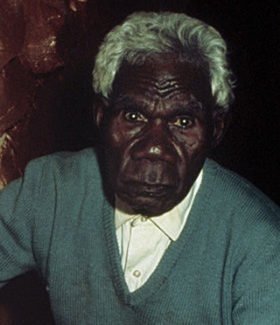

CHARLIE NUMBULMOORE

BIOGRAPHY

Charlie Numbulmoore lived for many years on Gibb River Station in the Central Kimberley where anthropologist Ian Crawford first recorded him repainting Wandjina figures in a Mamadai cave in the 1960’s. The few biographical details of Numbulmoore’s life that exist are traced solely through his encounters with those anthropologists who collected his work. Following Crawford’s initial encounter, Helen Groger collected the artist’s work on behalf of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in 1970, the same year that collector and grazier Tom McCourt purchased a number of paintings on bark, plywood, and cardboard. In his journal McCourt recollected Numbulmoore as 'the last of the old people here… who has that certain something that impresses you… when I was in Charlies camp, I bought several paintings he had in his hut from him… although his work is childlike, it has the primitive look of paintings seen under the rock hangings out in the bush' (cited in Sotheby’s 2003: 10). The Wandjina, exclusive to areas of the Kimberley, are said to have lain down in a cave and turned into a painting after their time on the earth. The Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Woonambal clans of the Kimberley are responsible for maintaining the remnants of these spirit ancestors. Numbulmoore’s paintings show a unique conception of the Wandjina, characterised by large round black eyes fringed with short delicate lashes. The centre of the chest features a solid black, or occasionally red, oval said to depict the sternum, or heart, or a pearl shell pendant representing its spiritual essence. The almost circular head is surrounded by a very regular, tripartite halo or headdress representing hair, clouds, and lightning. Unusual in these works is the inclusion of a mouth and a long narrow parallel-sided nose flared at the very tip with nostrils.

After retouching a Wandjina near Mamadai Charlie stated, 'I made you very good now…you must be very glad because I made yours eyes like new. That eye you know, like this my eye… I made them new for you people. My eye has life, and your eye has life too, because I made it new … don’t try bringing rain, my wife might drown with the rain' (cited in Ryan 1993). The reference to the Wandjina’s power over the rains is particularly pertinent for Numbulmoore. The inclusion of a mouth is distinctive of his work as this is rare in Wandjna depictions. That he does so illustrates how individual interpretations of Wandjina are unique to each clan. Their more common absence is most often attributed to a belief that painting a mouth on the Wandjina’s face would bring perpetual rain.

It has been suggested that Wandjina paintings on bark were first produced for trade and exchange with missionaries travelling by lugger along the coastline prior to mid 1970's. The Worrorra, Ngarinyin, and Woonambal artists did not possess the technical know-how commonly found in Arnhem Land. For this reason, their own barks were 'usually poorly prepared, the often knotty surfaces left irregular, and the pigments, applied without fixatives' (Ryan 1993: 15). Few of these pre-1970’s examples survive. However, Charlie Numbulmoore’s paintings are a rare exception to this, as along with bark, he employed unusual but more durable surfaces, such as slate, hardwood coolamons, or even cardboard. Notably, images of the Wandjina created on bark, canvas or slate were viewed by artists like Numbulmoore as purely reproductions of the ‘real’ Wandjina’s adorning the cave walls at their most important Dreaming sites. Their primary artistic inspiration and purpose lay in their responsibility to maintain the ancestral beings by repainting them and ‘keeping them strong’.

The great strength of Charlie Numbulmoore’s artistic legacy is that he was able to convey the aesthetic and spiritual power of the Wandjina undiminished through a range of portable media that survive to this day.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Dedman, Roger, Autumn 2006, ‘Market Profile Wandjina,’ Art and Australia, V. 43. No. 3.

Ryan, J., 1993, Images of Power, Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, exhib, cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Stanton, John E, Autumn 2006, Wandjina: The Wandjina figure is an archetypal image from Aboriginal rock art. Art and Australia, v.43 no.3: (414)-419.