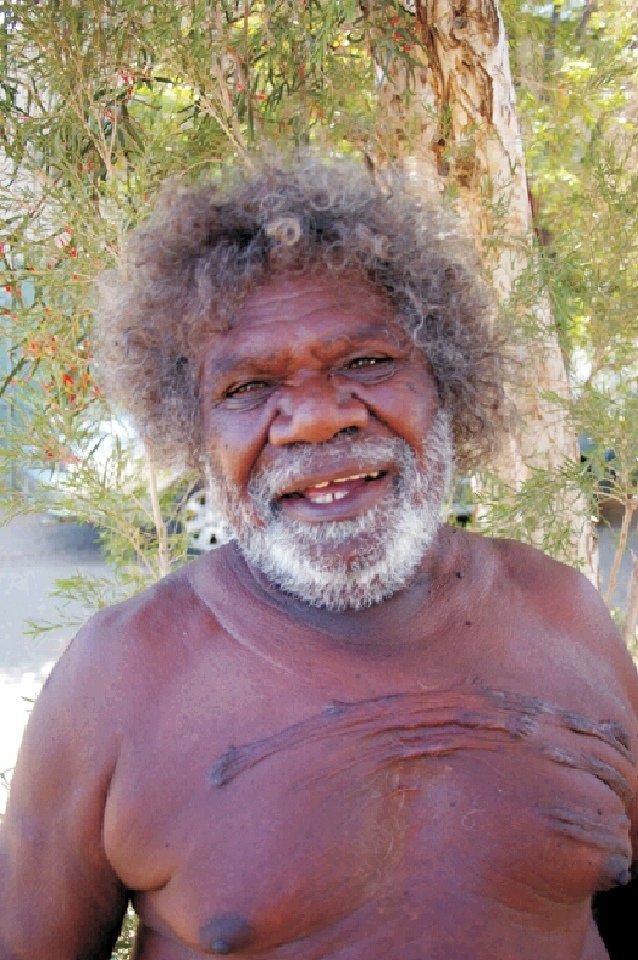

GEORGE (HAIRBRUSH) TJUNGURRAYI

BIOGRAPHY

Photo: Kate Owen Gallery

Born near the claypan and soakwater site of Wala Wala in the far reaches of the western desert George Tjungurrayi's initial contact with the outside world occurred as a seventeen-year-old boy. He left the Gibson Desert on foot in the company of three other Pintupi companions to walk the long road east until intercepted a truck just south of Mount Doreen. Soon after walking in to Papunya in 1962 he became a guide for Jeremy Long’s welfare patrol in to Pintupi country later that year and finally settled in West Camp, Papunya where he began painting around 1976 after encouragement from Nosepeg Tjupurrula. Over the following decade George worked intermittently at Yayayi and Mount Liebig, and also Walungurru. His works created during the 1970’s and throughout the 1980’s were characterized by the ubiquitous dotted grids of lines and circles common to works by Yala Yala Gibbs, Anatjari Tjamptjinpa and others who played a formative influence in Pintupi Tingari imagery. While painting at Papunya and its outstations in the late 1970s George worked in close proximity to these and other ‘established’ artists. It was not until well in to the mid 1980’s that he expanded his palette beyond the autumnal tones created by the basic palette of red, yellow, black and white by mixing in a wider array of colours and experimenting stylistically. His preoccupation from the outset had been the ceremonial activities and men’s stories associated with the travels of the Tingari ancestors as they relate to his most significant sites including his birthplace Wala Wala, and the region surrounding Kiwirrkura, Lake Mackay, Kulkuta, Karku, Ngaluwinyamana, and Kilpinya to the north-west of Kintore.

His painting first achieved prominence when exhibited in Friendly Country - Friendly People organized by Dick Kimber for at Araluen Arts Centre in Alice Springs in 1990. The work selected included the figurative representation of the Snake, Kunia, curled at Karrilwarra, its ancestral home. However, figuration in his work had always been rare and by 1994, George forsaken figurative imagery altogether in favour of works entirely composed of duotone linear roundels and shapes arranged in tight formal geometric patterns that pulsed with a subtle optical rhythm. His works had always suggested a sacred geometry related to topographic depictions of the sites visited by the Tingari, however from this period onward his paintings grew increasingly distanced stylistically from their ceremonial origins and the application of distinct dotted brush strokes.

Tjungurrayi depicts the Tingari Dreaming Cycle and the sacred sites of his ancestral history. However he departs from the characteristic style of Western Desert painting with its distinct dotted style, in his minimalist approach to iconography and by creating linear effects through the paint. In common with Ronnie Tjampitjinpa and Turkey Tolson, George experimented for a time with four panelled squares and rectangles before returning to transverse parallel lines that made eccentric deviations toward the margins of the painted surface. According to Judith Ryan the major Tingari Dreaming that Tjungurrayi created in 1996 now hanging in the National Gallery of Victoria marks the moment at which he reached the ‘conceptual distillation’ of his signature style. ‘The gently brushed pale mauve and plum lines create tonal reflections and visual sensations, like reverberations in a lake’. While the final work is duotone in appearance the artist has technically worked in four layers by painting and overpainting two shades of subtle colour with different pigment densities in quivering perfect parallel lines. The work, according to Ryan, became a template for his paintings that followed.

This stylistic departure from ceremonial origins was part of a larger movement of the Papunya Tula artists, which Rex Butler has described as fundamentally abstract and modernist. ‘The decisions Tjungurrayi makes in putting together his paintings are first of all artistic’ wrote Butler in 2004. (Butler: 2004, p113), Thus “it is not culturally specific; its specificity is that belonging to painting itself, “ (Butler: 2002, p2). Regardless of whether Tjungurrayi’s art along with that of Emily Kngwarreye for instance, is mediated by culture and history, or free of it, this approach to the act of painting itself has certainly been accepted in the art market. The work of a number of Papunya men including George, Willy Tjungurrayi, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, Mick Namarari and Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, can clearly be seen as a move away from traditional conventions. The magical power of these works draws on their original source, and primary influence, that of the ancient artistic lexicon inherent in the fluted carving, keyed designs, and fine parallel lines that embellish men’s ceremonial shields and sacred objects. They have no focus but invite the viewer to enter a crucial cultural performance. The energy and life-force enacted on to the painted surface evokes sensations and sensibilities that must primarily be experienced and felt. The eye of the viewer travels over the surface of these paintings, paralleling the way they move over nature. In doing so they are charged with an intensity that can become disorienting. While they continue to symbolize ancestral journeys and ceremonial body paint designs, they find immediate favour amongst collectors in an era of modernist globalism as they fit neatly with western notions of abstract minimalism and have serendipitous aesthetic parallels with works created contemporaneously by ‘Op-art’ and ‘simulationist’ artists such as Victor Vasarely, Ross Bleckner Phillip Taaffe, and Bridget Riley. As with the works of his Pintupi male contemporaries George Tjungurrayi’s works have no real focus yet they can be ‘inhabited, so that the mind’s eye, or the eye’s mind, can move about them credibly’. In common with early works by Riley, ‘nature is not landscape, but the dynamism of visual forces, an event rather than an appearance’.

George Tjungurrayi held his first solo exhibitions in 1997 at Utopia Art Sydney and in 1998 at Gallery Gabreille Pizzi in Melbourne following which Robert Rooney wrote a rave review in the Melbourne Age. By 2000 George Tjungurrayi had become one of Papunya Tula’s most sought after painters and was listed amongst Art Collector magazine’s 50 most collectable artists in 2003 the same year that he had been included on the exhibition Meridian, Focus on Contemporary Aboriginal Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. His work featured in the landmark exhibition Talking about Abstraction at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery in 2004, an exhibition intended to compare works by Western and Indigenous artists and examine the ways in which each was directly influenced by or resonant with the other. In 2006 he was highly commended 34th Alice Prize and the following year he was selected as a finalist in the Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. George Tjungurrayi’s work is held in many important international museums including the Groniger Museum in the Netherlands and the Musee des Arts d’Afrique et d’Oceanie in Paris. Alongside Ronnie Tjampitjinpa George Tjungurrayi has now become the principle living exponent of Pintupi men’s art.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Johnson, V “Seeing is Believing: A Brief history of Papunya Tula Artists 1971-2000,” in Papunya Tula Genesis and Genius, Perkins, H & Fink, H (eds), 2000

Butler, R. George Tjungurrayi, Unforseen Catalogue Fire-Works Gallery Queensland October 2002

Butler, R. Ronnie Tjampitjinpa & George Tjungurrayi, Spirit and Vision in Aboriginal Art, Trinker, B & Brizi, F (eds), Sammlung Essl 2004

Ryan, J. George Tjungurrayi, Art and Australia,Vol44 No. 4 Winter, 2007 p 582

Johnson, V. Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008