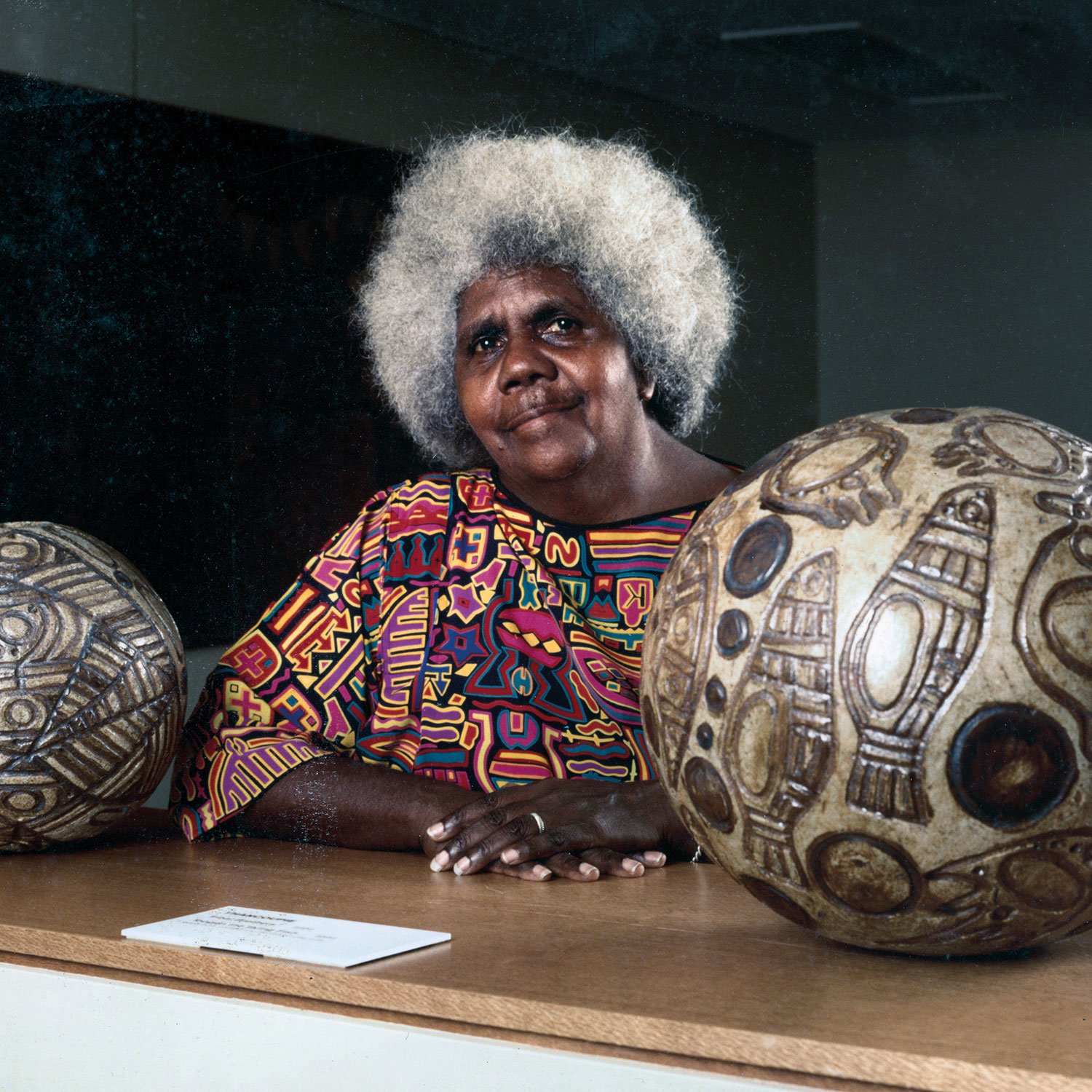

GLORIA FLETCHER THANCOUPIE

BIOGRAPHY

Image: Jennifer Isaacs and Effy Alexakis

Thancoupie, has been credited, along with Tiwi potter Eddy Puruntatamerri, as being the founders of Australia’s Indigenous ceramic art movement. Trained as a primary school teacher, she created her first artworks in ochres on bark. In 1971, when in her mid 30’s, she moved from her home in Weipa, Northern Queensland, to the urban environment of East Sydney Technical College and began training under the guidance of famed Australian ceramicist, Peter Rushforth, the head of the ceramics department at that time.

Drawn to ceramics, as clay was sacred a Weipa, and making art with it was somehow “strange but exciting,” (cited in Isaacs 1982: 35) her work was initially influenced by Japanese functional ware. During her training however she refined both the iconography and form of her work through a series of transformations, developing a unique style of hand-built large bowls, that gave way to spherical shapes, and later, to more organic and minimal forms that were more closely drawn from nature. This “exploration in ceramics came as a sort of freedom or a revelation to her, as she met and mixed with people in the artistic world,” (Isaacs cited in Message Stick: 2004). Indeed the relationships Thancoupie formed played an influential role in her artistic practice. At this early stage in her development as an artist, the elegant simplicity of her line and brushwork, representing animals and her traditional creation stories, evolved from working with her teacher, the Japanese potter Shiga Shigeo. Not only was her artistic practice influenced by prominent friendships, but also the manner in which she chose inter-act with the art world, “to exhibit with the best artists, sculptors and craft-makers,” (Kleinert & Neale 2000: 713), as a contemporary artist, rather than an Aboriginal Australian artist. In 1983 she visited Sao Paulo as Australia’s Cultural Commissioner to the 17th Biennale and her works subsequently toured Brazil and Mexico. It was later included in the Portsmouth Festival in the UK.

The primary focus throughout Thancoupie’s distinguished career has been on the ‘object as art’. Her naturalistic forms, the methods of making them, and the incised decoration that adorns the surface, relate these objects directly to traditional ways of story telling. (Newstead, 2003). Her forms are created by building with slabs and using the concave surfaces of her own body, her knees and elbows to push the walls of clay in to free-form shapes. Large spheres and ‘eggs’ are created using semi circular moulds as a template and then building upon the shapes created with small pieces of clay from the inside out as the walls rear up from the mould. Thancoupie’s surface decoration, in which Thainkuith legends and totemic creatures are illustrated by grooving the surface, demonstrates the connection between her work and traditional sand drawing (Watson, 1999). Her sculptural pieces assert the three dimensional quality common to Australian Aboriginal painting by which it differs from the European concept of painting as a two dimensional activity. In her work important Dreaming narratives, for generations held precariously in song and living memory are encoded alchemically in rock-like permanence from the numinous materials of clay and pigment. In creating this visual language, combining the ceramic shape with the etched surface decoration, she has produced pots of great beauty and, in the process, has become regarded as one of Australia’s great artists.

Thancoupie’s creative influence can be compared to that of the great Native American Pueblo artist Maria Martinez in that it has provided the impetus for the development of the Indigenous ceramic art movement in this country. Yet her prime motivation has steadfastly remained a personal one. Her unique personal interaction with artists from a range of creative disciplines here in Australia and overseas has served only to strengthen her intimate relationship with her own culture. Over the past 30 years she has mentored aspiring artists from communities in Far North Queensland, Arnhem Land, the desert and the Tiwi Islands; Indigenous and non-Indigenous students enrolled in art and professional development courses; and others in her extensive travels as an artist of international acclaim. Her commitment to teaching spilled beyond her art, founding the Weipa Festival and running holiday programs to teach bush knowledge and art to younger generations. Thancoupie’s creative and philosophical motivation carries a universal message best expressed in her own words. “You are here in a lifetime to help, to understand… That is intelligence. And only intelligent people have strong friendships. I wish we all have that,” (Message Stick: 2004).

© Adrian Newstead

References

Art and Aboriginality, Australia, 1987, Catalogue of the Exhibition, Portsmouth Festival UK, Aspex Gallery

Isaacs, J., 1982, Thancoupie the Potter, Aboriginal Artists Agency, Sydney.

Johnson, T. March 2002.’ Thancoupie’ Art and Australia. V. 39. No. 3: 380-381.

Kleinert & Neale. 2000. The Oxford companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, Australian National University, Australia.

Maza. R. 5 November 2004. Message Stick ABC Television. ‘Thancoupie.’ : Online: www.abc.net.au/message/tv/ms/s1175226.htm.

Newstead A, 2003, A Survey of Australian Indigenous Ceramic Art, Ceramics Art and Perception, Paddington, NSW

Watson C.,1999 Touching the Land, in Art From the Land, dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal Art, Morphy H. and Smith Boles. M. University of Virginia,