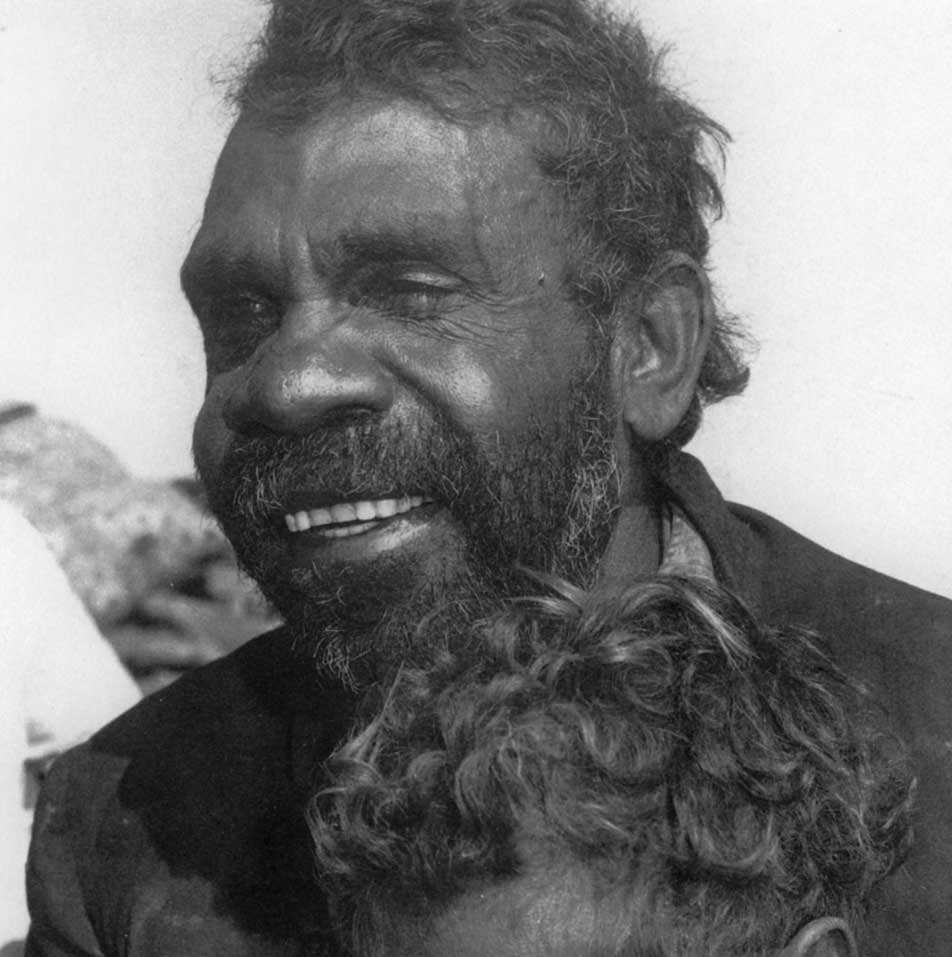

KAAPA MBITJANA TJAMPITJINPA

BIOGRAPHY

Photo: Allan Scott

Although born west of Napperby at the Emu Dreaming site of Altijira, Kaapa’s father’s country lay to the west at Warlurkulangu, the ancestral bushfire site in Warlpiri country, while his mother was Anmatjerre/Arrernte from further east. After a year of seclusion during initiation at Napperby he became a stockman at the adjacent Mount Allan station and subsequently worked cattle in what was a physically demanding and often-dangerous life. After a period droving cattle between the Tanami desert and Mount Isa in North Queensland he settled for a time in Haasts Bluff along with his younger ‘brother’ Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa and their cousins Tim Leura, Clifford Possum and Billy Stockman with whom he had grown up.

After the entire community was moved to Papunya in the late1950’s, due in part to the lack of potable water, Kaapa became renowned, at least by the white authorities, as a disruptive influence and was said to have been involved in a number of activities involving grog running and antisocial behaviour and at the time of Geoffrey Bardon’s arrival at Papunya in 1970, he was considered by police officers at Papunya to be an “incorrigible drunk and unsettling influence”. Even Bardon described him in 1970 as a ‘two legged human swag’ (cited in Johnson, 2008) however it wasn’t long before he came to consider Kaapa a highly intelligent and gifted man who, like many of his tribes folk, had been intimidated by whites and been set adrift from his cultural roots when his traditional lands were divided up for European cattle stations.

Yet even before the contemporary art movement began in 1971, Aboriginal community members already respected Kaapa as an important artist, who was often called upon to paint ceremonial objects for Anmatjerre and Arrernte tribal purposes. (Bardon, 1991, 37). He had been painting watercolour landscapes in a ‘Hermannsburg school’ style before Bardon arrived and was amongst the first to begin working with him. It was not surprising therefore, that when the older men came together to paint the Honey Ant mural on the school wall, Kaapa was immediately appointed their leader and the enthusiasm of the group painting the mural became focused through Kaapa’s already accomplished skills and his singular creative commitment.

Bardon had been unsuccessfully trying to encourage the school children to paint the traditional patterns he had seen them drawing in the playground sand. The idea of the mural soon attracted the attention of the older men and Bardon quickly realized that, in keeping with cultural values, he had to be ‘given’ a design by the tribal law givers. The subject matter had to be agreed upon as acceptable for general viewing and not trespass upon the secret, sacred imagery that in Aboriginal society provides the vehicle for social and spiritual initiation. The Honey Ant is a mythical ancestor who emerges from the ground and moves across it, creating the landforms which young children are taught to recognize as part of their familiar terrain. Bardon questioned Kaapa’s first honey ant, as it appeared on the wall in what seemed to follow a Europe style depiction: “Not ours”, Kaapa told him, “yours.” “Well paint yours!” Bardon replied, “Aboriginal honey ants!”

It was after this brief exchange and following a whispered consultation with the other men, Bardon recalled, that the authentic Honey Ant ‘hieroglyph’ appeared with its true traveling marks around it, painted lovingly by Kaapa with his deft and sinuous hand. There was cheering and rejoicing from the gathering crowd and, as Bardon later wrote, “This was the beginning of the Western Desert painting movement…Something strange and marvelous was set in motion.” (Bardon1991, 21)

Kaapa was a charismatic figure, yet he needed encouragement at first to reveal his true self. He did not trust white people. They had mocked his artistic endeavors in the past and he was initially hesitant to become a member of the new painting group. His extraverted bravado had facilitated his survival in often harsh and unfriendly conditions but sometimes it fell aside to reveal a miserable discontent. Over and above this dilemma however, Kaapa nurtured a unique sense of vocation as an artist in his own right, seeking out the best materials, ascertaining his own position and unlike the others, signing his works from the very start. His natural talent and skilled technical ability was recognized when he surprised the Northern Territory art world by becoming the first Aboriginal to win the Alice Springs Caltex Golden Jubilee Art Award, 1971. A spate of sales followed and the jubilant painting group elected him founding chairman of Papunya Tula Artists in 1972. It was he who held the key to the painting room, arriving early to keep a check on supplies and setting himself up at his regular spot, facing the door, ready to talk to visitors or working with immense concentration at the only table and chair. He was a central figure during the company’s first decade and, despite failing to maintain the same level of intimate intensity and detail in his works post 1975, he remained influential amongst Papunya-based painters throughout the rest of his life. (Bardon, 200, 201)

Kaapa’s early paintings show designs and motifs painted on a plain black or orange ochre background, including realistic figures, finely decorated with body paint as well as ceremonial objects such as shields, spears and ceremonial boards. Early collectors were keen on Kaapa’s graphic clarity and symmetry of design. His ability to paint intimate details with the brush and to build an ordered sense of story appealed to European sensibilities. Yet over the years following Bardon’s departure, the confluence of artists, advisors and widening public reaction propelled developments in painting at Papunya towards a less representational, evolving modern style. Ancient Dreaming myths that had traditionally been told through song, dance and ground painting could not transfer literally to paintings on board and canvas without revealing restricted ceremonial knowledge. Kaapa was encouraged by Bardon and subsequent art advisors, to concentrate on the essentials of a story, still infusing it with the rhythm of its telling, but without revealing secret or specific details. In doing so much of the power and authority inherent in Kaapa’s subsequent works was dissipated under the veil of dots, which became more prevalent. At first the dots were used to conceal sacred references but more often they were used to emphasize design elements or create a sense of grounding. These subsequent works were popular at the time as Kaapa’s renown grew, but time has revealed these to be far less successful artistically.

Kaapa’s greatest artistic legacy was the monumental Budgerigar series 1972, which negotiated a very close line between the secret and the secular. A characteristic dynamic of balances and counterbalances magnifies a powerful sense of presence in these paintings that confirmed his status as a master artist. Detailed brushwork captivates the viewer with a precise visual vocabulary, every stroke vibrating with life and purpose. The much loved tales of the tiny, colourful birds that chirp and flutter around desert waterholes after rain, give full expression in these paintings to Kaapa’s love of spectacle. These works clearly demonstrate that the changing expectations of others, in relation to his painting, never deeply disturbed his own “driven and creative” trajectory. (Bardon, 2004, 281) Kaapa continued to test the boundaries of his art until his death in Alice Springs in 1989. He was one of the first desert artists to be openly assisted by his female relatives in the completion of his works during the 1980’s. While art advisers and observers expressed concern Kaapa’s status as a highly respected elder, saw him brush these Eurocentric concerns aside as he insisted that this was entirely consistent with Anmatjerre law and cultural practice. However his works of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s with their floral backgrounds and decorative content have not stood the test of time.

Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa was an artist of the highest importance in the development of Western Desert art. During the early 1970’s he created, “some of the most powerful and emblematic paintings from the Central Desert” (Kean, 1990, 567). Yet it is for his early works that he renown endures. The finest examples are held in major collections throughout Australia, and overseas and these remain his greatest and most enduring legacy.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya, A Place Made After the Story, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2004.

Bardon, Geoffrey, Papunya Tula, Art of the Western Desert, Penguin books Australia, 1991.

Bardon, Geoffrey, “The Money Belongs to the Ancestors” in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink (eds), Art Gallery of NSW, 2000.

Corbally Stourton, Patrick, Songlines and Dreamings, Lund Humphreys Publishers Ltd, London, 1996.

Johnson, Vivien, Dreamings of the Desert, Aboriginal Dot Paintings of the Western Desert, Art Gallery of South Australia, 1996.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Kean, John, “Obituary” in Art and Australia, vol 27, No. 4 , 1990.