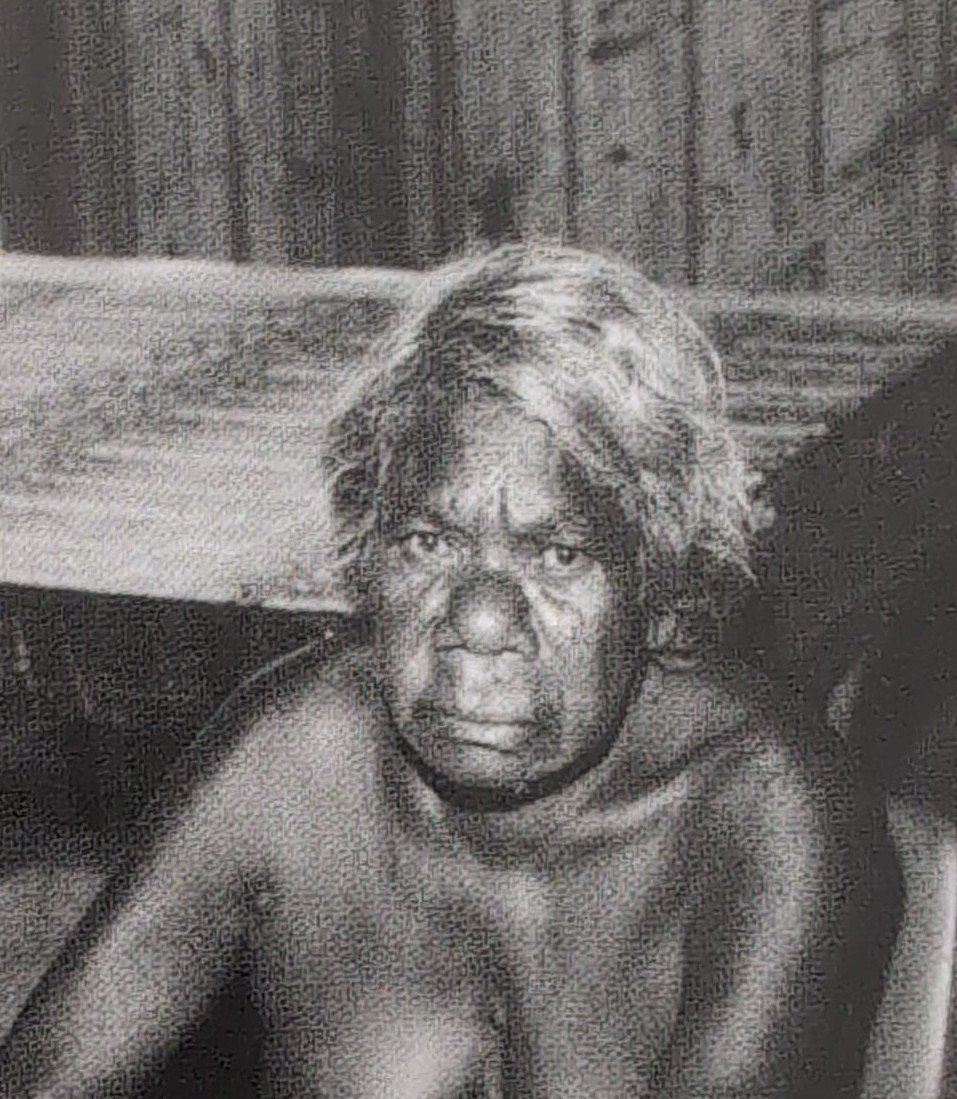

KITTY KANTILLA

BIOGRAPHY

Kitty Kantilla, was born c1928 at Yimpinari, on the Eastern side of Melville Island, and lived a traditional life as a child, only exchanging the paperbark roof of her youth for mission life in her adulthood. The mission settlement located on the eastern coast of Bathurst Island some 100 kilometres across the waters to the north of Darwin had been established in 1911 and those who worked in the mission received rations like beef, flour, honey and tea which supplemented their bush tucker. In 1970 Kitty, along with a number of other countrywomen created a tiny outstation in her mother’s country at Paru, on Melville Island, just across the waters of the Aspley Stait within sight of the growing township of Nguiu. It was here that Kitty first began working as an artist, as one of a group of widowed women who became renowned during the early 1980’s for their iron wood sculptures of ancestor figures drawn from the Purukupali legend.

By the late 1970’s the pottery established that had been established in Darwin at the Bagot reserve by Eddy Puruntatamerri and others, had been reestablished in Nguiu and this was joined, in 1978, by Tiwi Pima Art, which encouraged the production of traditional arts including wood carving, bark painting and weaving. In the early 1980’s a fabric printing facility, Tiwi Design was established and by 1985 all three enterprises came under the same management. The ‘Paru Women’ sold their work through this facility on Bathurst Island until, by the early 1990’s, most of them had passed away. Without their support and friendship, Kitty moved in to Milikapiti (Snake Bay), where Jilamara Arts and Crafts had grown from an Adult Education centre supporting more and more artists who lived closer to their own ‘country’. Here as she grew older, she ventured away from sculpture and began working on canvas and paper.

The roots of Kitty Kantilla’s art, regardless of medium, was always tied to the fundamental Tiwi creation story. This classic morality tale is the equivalent in Tiwi Culture, to that of the Ramayana or Mahabarata in Asian and India, or Adam and Eve and their fall from grace amongst Christians. In the Tiwi version of creation Bima, the wife of Purukapali, makes love to her brother in law, while her son Jinani, left lying under a tree in the sun, dies of exposure. Purukapali becomes enraged and after his wife is transformed into a night curlew he begins an elaborate mourning ceremony for his son. This was the first Pukumani (mortuary) ceremony, and tells how death first came to the Tiwi Islands. It remains at the centre of Tiwi culture to this day, “as a nucleus for the entire Tiwi world-view,” (McDonald). Kitty Kantilla’s art, and indeed all Tiwi art, is informed by the ornate body painting of the Pukumani ceremony. What makes the art of Kitty Kantilla and those of her generation so inherently important is that the meaning of these designs characterized by abstract patterns made up of dots and lines has been largely lost since the missionary era. She, was amongst the very last who inherited these designs intact from her father. In her own words, ‘I watched him as a young girl and I’ve still got the design in my head’ (Ryan 2004: 394).

In the early period of Kantilla’s works on paper and canvas her style consisted of white, red and yellow dots against a black background. The fields of dots were punctuated solely by bands of solid colour or geometric shapes. By 1997 she began painting on to a white background, thereby reversing the colour dynamics and energy of her works. Her style varied once more in 2002, when she began to employ large blocks of textured colour, punctuated by small segments of dots and lines on both black and white underlay. This subtle mastery over abstraction, anchored to the very essence of her culture, and the trembling impression of her marks at this late stage of her life, evoked the kinetic movement of participants as they sang and danced during ceremony. This was only heightened by her exquisite attention to detail. Art critic Sebastian Smee most aptly described Kitty Kantilla as ‘a poet of small scale contrasts,’ (2000: 22). In her final years, though frail, she could imbue her works, despite their lack of figuration, with her mixed feelings about the passing of the old ways and the uncertainty about the new. Her art practice and her reputation during the last decade of her life was greatly enhanced by the very special relationship she shared with Gabriella Roy who promoted her as an artist of renown, and the regular solo exhibitions of her work held at Roy’s Aboriginal and Pacific Gallery in Sydney. In 2000 Kitty participated in the Adelaide Biennale of Australian Art, and in 2002 she won the works on paper award at the 19th Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Awards in Darwin. Kitty Kantilla, was honoured with a posthumous retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria which opened in 2007 and toured nationally.

© Adrian Newstead

References

McDonald, John, Mar-Apr-May 2003, ‘Pumpuni Jilamara: Tiwi Art,’ Art and Australia, v.40, no.3,: 394-395.

Ryan, Judith, Autumn 2004, ‘Kutuwalumi Purawarrumpatu,’ Art and Australia, v41, no. 3: 394.

Smee, Sebastian, 22 December 2000, ‘The Poet of Small Things,’ Sydney Morning Herald: 22.