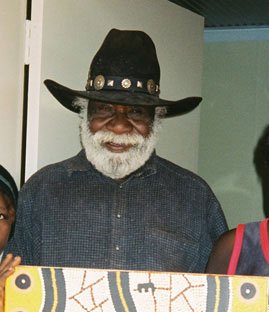

LONG JACK PHILLIPUS TJAKAMARRA

BIOGRAPHY

Photo: National Museum Australia

A tall man, of ‘fine bearing’ as art teacher Geoff Bardon described him, Long Jack Phillipus was one of Bardon’s original group of ‘painting men’. Born at the important Rain Dreaming site of Kalipinypa, north-east of Kintore, he grew up in the bush and ‘came in’ with other family members to Haasts Bluff as a teenager in the late 1950’s after the death of his mother. He worked as a stockman and later, when he settled at Papunya, as a school yardsman and community councilor. He was competent in his dealings with white people and always a productive worker but also knew a lot about Aboriginal law and loved to ‘go bush’ on hunting expeditions at any opportunity. His reflective nature prompted his interest in Christianity and possibly protected him from the ravages of alcohol that beset many of his hard-drinking friends. In 1984 he became ordained as a Lutheran pastor, finding Christianity quite compatible with his traditional spiritual beliefs. He was always alert to the conflicts that swept through the Papunya settlement where four tribal groups from a huge desert area had been re-settled with their resulting difficulties in adjusting to a European lifestyle.

Long Jack Phillipus was an instrumental member of the group involved in creating the famous mural that marked the beginning of the contemporary western desert art movement. He participated in the secret discussions amongst the senior law men and later told Bardon that the Honey Ant design was a gift, ‘given to the white man’s school’ by ceremonial leaders of the Aboriginal people. As school yardsman, Long Jack Phillipus, prepared the walls with cement rendering and coats of white primer and then later assisted Kaapa Tjampitjinpa and Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri in the mural painting itself. Amongst the enthusiastic group that began to paint regularly at the back of the school art room, Long Jack’s work was some of the first to sell in Alice Springs, spurring the other men on in their efforts and commitment. Long Jack shared close ties over Kalipinypa with ‘Old’ Walter Tjampitjinpa and Johnny Warangkula and was the owner of Ngamarunya, the principal Possum Dreaming site in the Gibson Desert, which featured strongly as a subject of his art. His painting style appealed to the public with its symmetrical balance and stylised figurative elements and he became one of the foundation members of Papunya Tula Artists. While he leaned towards a softer, slightly more decorative approach, by using the traditional earth colours in more harmonious ways than a number of the other men, he still achieved the striking effects that first grabbed the attention of the Australian art world during the early years of the art movement.

A change of government in 1972 brought in a new era of interest and funding for cultural activities throughout Australia, resulting in the establishment of the Australia Council for the Arts and it’s Aboriginal Arts Board. Long Jack, who had lived in Papunya since 1962, was part of a delegation of Papunya artists who went to Sydney to provide advice and support on new policies that encouraged self-determination amongst Aboriginal communities. The participants were conscious of themselves as part of an ‘art movement’ (Johnson V, 2000, p191) the force of their communal creativity generating a positive influence individually but even more importantly, upon their wider cultural identity. When criticism appeared in the media, the group prepared a reply; “We are not ‘ turning our heritage into cash’ -we want the whole world to know of our culture,’ they claimed. ‘We keep our ‘sacred heritage’ for ourselves, for our ceremonies and for our children’… The paintings show our stories but only non-sacred stories. The designs we use are the designs we have always used.’ (Johnson V, 2000,p 188) The process of refining the contemporary style had not proceeded without controversy. Bardon had encouraged the men to paint children’s stories after conflict had arisen between tribal groups regarding secret sacred material being revealed to the art buying public. Because of the discord that often prevailed at Papunya, lives could be put in danger if tribal law was infringed. The simple intelligibility of these introductory stories brought different backgrounds and interests together in a straightforward relationship between mark and message. Sacred references were disguised or abstracted so that an uninitiated viewer could not decipher them. Long Jack helped Bardon to comprehend the important issue of tribal and personal custody of Dreamings. He also took a lead in stepping away from problematic subjects with his paintings of the Kadaitcha Dreaming 1972, the feared and invisible spirit who punishes wayward children, and many Water Dreamings which tell of the wondrous, life-giving effects of rain in the desert. During the early 1970’s Long Jack served on the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council and created some of Papunya Tula’s largest early canvases for the board’s overseas exhibition program (Johnson, 2008, p13).

Although he was awarded first prize in the Northern Territory Golden Jubilee Art Award in 1983 and took out first prize in the Alice Art award the following year Long Jack found it difficult to make the transition during the late 1980’s and 1990’s to an equally appealing esthetic minimalism as a number of his contemporaries. While he continued painting for Papuya Tula for many years he was instrumental along with Paddy Carroll Tjungurrayi, William Sandy, Dinny Nolan Tjampitjimpa and others in supporting the Papunya Community Council when it established Warumpi Arts as an alternative support organization and retail outlet for artists continuing to live in the Papunya Community. Warumpi Arts operated a gallery in Alice Springs throughout the 1990’s and Long Jack’s works were regularly featured there. It is likely that his defection from Papunya Tula was born of his frustration at seeing the work of a number of his contemporaries as well as that of other, younger and emerging artists sell more regularly and at higher prices than his own. Never-the-less his paintings produced for Papunya Tula are undoubtedly his best works and it was principally though his association with the company that he regularly participated in important landmark exhibitions throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s including The Face of the Centre, Mythscapes, and Power of the Land all curated by the National Gallery of Victoria. His early works are represented in many impressive and important collections and will always demand the greatest attention. While he has continued to paint throughout the 1990’s and beyond Long Jack Phillipus will be remembered principally for his leading role during the emergence of the movement. His late career works have been less popular and successful than those produced during the 1980’s yet they have enabled Long Jack, now in his late seventies to provide a steady source of financial support and encouragement to his large and extended family.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya; A Place Made After the Story, The Beginning of the Western Desert Painting Movement, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, Australia, 2004.

Carter, Paul, “The Enigma of a Homeland Place, Mobilising the Papunya Tula painting movement 1971-1972 in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, edited by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Art Gallery of NSW, 2000.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Myers, Fred, Painting Culture, The Making of an Aboriginal High Art, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2002.