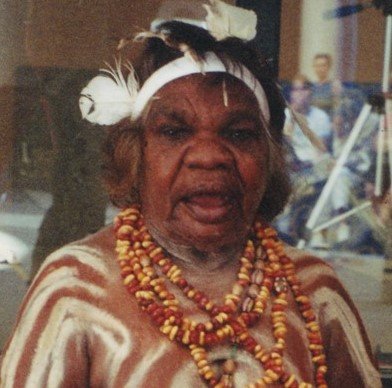

LORNA FENCER NAPURRURLA

BIOGRAPHY

Born c. 1925, at Yarturlu Yarturlu, a Yam Dreaming site, Lorna Fencer, was the custodian of inherited land Yumurrpa situated near Chilla Well, south of the Granites Mine in the Tanami Desert. Her father’s country was Wapurtali. She spent her early years living a traditional life until, in 1949 she, along with many of her Warlpiri countrymen, were forcibly transported to the government settlement of Lajamanu at Hooker Creek, situated in the country of the Gurindji people. Lajamanu lay 250 miles north of the traditional Warlpiri homelands and it became a disconsolate community, as its governance during the 1950’s was militant and suppressive. Many Walrpiri walked the 800 km back to Yuendumu only to be forcibly returned once more, thereby creating a deep sense of disempowerment and loss. Despite this, the Warlpiri elders kept their customs and ceremonies alive with a fierce determination. Lorna Napurrula in particular maintained and strengthened her cultural identity through ceremonial activity thereby asserting her position as a prominent elder and teacher in the community.

Aware of the growing popularity of painting amongst the Pintupi and other groups in the western desert, the Warlpiri men of Lajamanu were deeply concerned and determined to safeguard secret and sacred Warlpiri knowledge. In 1983, 12 Warlpiri men from Lajamanu and Yuendumu traveled to Paris to create a traditional sand-painting and dance at the Musee d’Art Moderne, however they were still strongly opposed to committing these designs to any permanent medium. However 3 years later, the Warlpiri position changed as a result of an adult education course run by John Quinn during which western art materials and methods were introduced at the local school. As this artistic activity strengthened, the women in particular were encouraged by the much-needed income that painting could provide and the role art could play as a means of preserving and maintaining their culture. Due perhaps to their dislocation from their own country to the south, the way that income from art had enabled the Pintupi who initially lived at Papunya to re-establish their links to country closer to Lake MacKay, resonated strongly with their own hopes and desires for a better future. The women of Lajamanu in particular were anxious to see their children provided with some source of spiritual grounding in the face of so many modern influences and distractions. However Lajamanu's isolation, due to its great distance from the urban art centres and the difficulty of communication with the outside world slowed the public emergence of Lajamanu art significantly. As late as 1989, there were still no telephones to connect the inhabitants of the community with the outside world. However, the arrival of a satellite dish from Yuendumu resulted in a teleconference link up in which I, as the director of Coo-ee Gallery in Sydney, my curator Christine Watson, and Allan Warrie of the Aboriginal Arts Board, sat in an Aussat teleconference room in Sydney’s Terry Hills while Abie Jangala, Lorna Fencer and other Lajamanu artists presented their work and arranged to participate in an exhibition during the following year.

Soon after the women began painting in 1986 they began to outnumber their male counterparts. The ‘hitherto sleeping giants of the Aboriginal Art world’, as Judith Ryan called them (Ryan, 2004, p.104), produced works that were astoundingly inventive and bold. Amongst them, Lorna Fencer stood out. Her powerful, gestural brushstrokes and uninhibited and bold and intuitive application of colour produced haptic effects in works characterized by fluidity and movement. The classical dotted infill never suited her whimsical nature and unique vision of Warlpiri culture. She adored colour and would sit solidly on the ground, painting with urgency until her pot of paint was depleted. Then, in the middle of this storm of creativity she would pick up the empty pot. ‘Orangy Orangy’ she would insist as if she could wait not a second longer for a refill of that sensuous liquid yellow paint. Her completed paintings executed in vivid yellows, pinks, purples, lime greens and brilliant reds pick up on the bursts of thousands of tiny blooms that fill the desert after rain, emphasizing them in an exuberant ‘celebration of pure painting’. Her more expressive, modernist style has an impulsive, organic logic to it, mirroring the plant or root structures of desert bush tucker.

Lorna was the custodian the sacred country of Yumurrpa and for the Yarla (bush potato), Luju (caterpillar), Bush Tomato, Onion and Plum Dreamings, many different seeds and, importantly, spring water for the Napurrurla-Jupurrurla and Jakamarra-Nakamarra skin groups. She also had ancestral rights over the Water Snake, which become numerous when the country is in flood, the riverbeds and claypans fill with water. She painted these as sinuous lines upon a watery expanse of liquid colour. Her paintings reflected the traditional stories of Ancestral women journeying through the bush, singing and dancing as they collected food. Sometimes her female ancestors would come upon a caterpillar, ‘that cheeky one’ that bites them while they are picking fruit, making them itchy. In other works Lorna would paint the digging sticks they used to find the bush potato or yam that spread underground in a meandering complex of roots and bulbs, a primary source of foot in their arid homeland.

Apart from brief periods during the early and late 1990’s , the Warnayaka Art Centre at Lajamanu has been extremely poorly served by the Aboriginal arts bureaucracy. After John Quinn’s departure, the art centre was run on a voluntary basis by the wife of the administrator, Lava Watts, with assistance from Valda Dixon and later by Brent Hocking. During intermittent periods between the late 1980’s and the end of the 1990’s artworks were supplied through the art centre for exhibitions with Gabriele Pizzi, William Mora, and Alcaston Galleries in Melbourne, Coo-ee Aboriginal Art in Sydney and Sharon Monty in Perth. However by the end of the 1990’s the art centre had fallen in to decline due to lack of funding and, following meetings with all of the stakeholders, I personally proposed that the Lajamanu Council fund the coordinators position on a 3 month trial basis. Vanessa McRae was appointed art adviser however, this failed once more to establish the art centre on a secure footing. Lorna Fencer painted throughout this period alongside Lilly Hargeaves, the Rockman sisters, Abie Jangala and others, working for the art centre when it operated, and for private dealers when it did not.

In particular Lorna, happy to live in the Warlpiri camp in Katherine would paint wherever the supply of paint and canvas would enable her to do so. In Katherine she worked for Alex and Petrina Ariston, owners of Katherine Art Gallery, with Mimi Arts and Crafts , with Mike Mitchell and others. She worked in Sydney during the Olympic Games and later, after returning to Katherine began producing a large body of work with the support and financial encouragement of David Wroth of Japingka Gallery in Fremantle. The quality of her works depended greatly on who she worked with and the materials that were supplied to her, nevertheless, despite the difficulties she faced as a practicing artist she was able to produce a high proportion of extremely accomplished and highly original works for more than 30 group exhibitions and 10 solo shows over a 15 year period. Beside the galleries mentioned above, solo exhibitions were held at Chapman Gallery in Canberra, Vivien Anderson Gallery in Melbourne, and Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland, New Zealand.

Lorna Fencer Napurrula’s lively and brightly coloured paintings, injected new energy into the living tradition of desert art. Her sheer joy and vitality when painting was a constant re-affirmation of the restorative spiritual power of traditional desert life. Lorna’s late career works, created in her 80’s are a revelation. The combination of her unrivalled knowledge of tribal lore and Dreamings along with her intuitive use of colour and free gestural brush strokes in telling her stories, lead to comparisons with the late Emily Kngwarreye, yet Lorna’s work was decidedly and uniquely her own. At her best she mastered colour, carefully considering its impact before laying it down on the canvas. Her large epic canvases created in the eighth decade of her life were final and compelling statements about the power of the great Warlpiri stories that she painted for over twenty years.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Newstead, Adrian, exhibition notes from Cooee Gallery and interviews with the artist

Ryan, Judith, Colour Power, National Gallery of Victoria, 2004

Plunkett Ian, exhibition notes, Japingka Gallery