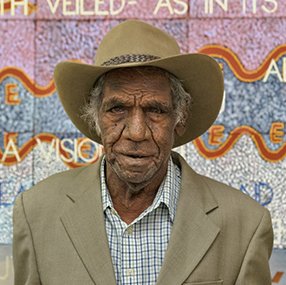

MICHAEL NELSON TJAKAMARRA

BIOGRAPHY

Photo: Mick Richards

Born at Vaughan Springs (Mt. Doreen Station), 100 kilometers west of Yuendumu, where a string of twenty-four freshwater springs support a flourishing desert oasis, Nelson was frightened by his first sight of white men as a young boy and remembers hiding from them in the bush. His family lived for a time at Haast's Bluff with the same family group as Long Jack Phillipus and later moved to Yuendumu so that he could receive European education at the mission school. He left at thirteen, after his initiation, and worked buffalo shooting in 1962 on the East and South Alligator Rivers, driving trucks, droving cattle and in the army, before returning to Warlpiri country at Lajamanu and later Yuendumu and, in 1976, moving to Papunya where he settled and married.

Michael Nelson had inherited key responsibilities for many sacred sites and rituals from his father, an important Warlpiri 'Medicine Man' at Yuendumu. The Warlpiri were deeply concerned about the painting movement that had begun at Papunya and while he worked in the government store and for the Council he observed the work of the older artists with interest. Despite the Warlpiri elders’ opposition to committing their sacred designs to canvas, the financial benefits were becoming increasingly evident to many of the far-flung desert communities. Nelson’s interest and early artistic efforts, made under the guidance of the older artists, was rewarded when in 1983 he was asked to join Papunya Artists as a full-time member. Though working within the carefully delineated, ‘classic’, style of the late1970’s and early 1980’s, his natural flair for inventive composition and zestful colour brought him to prominence when in 1984 he won the inaugural National Aboriginal Art Award and two years later exhibited in the Biennale of Sydney. In 1987, Western Desert art proclaimed its place within the nation’s identity when his 8.2 metre mural was installed in the northern foyer of the Sydney Opera House. He was introduced to the Queen at the opening of Australia’s new Parliament House the following year having designed the 196 square metre mosaic that dominates the forecourt of the building.

If ‘timing is everything’, then, as Nelson’s long time friend and biographer Vivian Johnson suggests, Nelson’s entry into the limelight was opportune. During the 1980’s, the evolving desert style gradually leaned away from the map-like sites and journey lines, to focus more on experimentation with design elements. Nelson found his forte in this era of aesthetic exploration. The growing awareness of Aboriginal art’s contemporary significance, nationally and internationally, fuelled public acclaim and Nelson traveled widely as one of the faces that presented, and at times demonstrated, this ancient art form to the world in its new mode.

His Five Stories, 1985, was reproduced on the cover of the catalogue/book that accompanied the exhibition Dreamings: Art of Aboriginal Australia that opened in New York in 1988. The year following his visit to the USA with Billy Stockman for the opening of Dreamings he had his first solo exhibition at Gallery Gabrielle Pizzi in Melbourne and painted a BMW M3 Racing Car. In this and other major projects at the time he was assisted on the dotting by his wife Marjorie Napaltjarri. In 1993, following two more solo exhibitions organised through Papunya Tula Artists, and his participation in Aratjara, Art of the First Australians he received the Order of Australia Medal for services to Aboriginal art, and a year later he was granted a Fellowship from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council.

At the same time as the burgeoning industry was putting more money in to remote Aboriginal communities it began to spawn a growing band of astute intellectuals and high-flying entrepreneurs. This gave rise to the ever-present anxiety amongst Indigenous custodians of trespassing too closely on secret-sacred tradition or commercialising it as a fashionable commodity. In view of the changing demands of modern times, Nelson publicly countered skeptics with a deceptively simple observation when he said ‘ the stories are the same but our way of telling them is changing’. In this comment he revealed that for him, the Dreaming remained a sacrosanct inner reality that no external circumstances could touch.

Despite this, by the mid 1990’s, following the heavy demand for is works during the previous decade, the pressure appeared to have taken its toll on him and his works became more stilted and formulaic. Other Papunya artists had begun developing less iconographically dependent, more abstracted, imagery that fitted the new emerging contemporary aesthetic. By comparison Michael Nelsons paintings seemed to have lost their zing.

In relation to the art political divide between art centres, independent dealers and individual artist entrepreneurship Michael Nelson Tjakamarra is the ultimate enigma. During the 1990’s he supported and supplied paintings to Warumpi Arts, an outlet set up in Gregory Terrace, Alice Springs, by the Papunya Community Council in direct competition with Papunya Tula. He was, if fact, elected president of the Papunya Community Council during the 1990’s and again between 2002 and 2004. And in 1996, having met artist and gallery owner Michael Eather in the late 1980’s, Nelson began formally working within the collaborative atmosphere of Brisbane’s Campfire Group in which an exchange of artistic ideas and practices flourished. As a result he participated with Paddy Carroll Tjungurrayi in the 2nd Asia Pacific Triennial at the Queensland Art Gallery.

Following a series of experimental workshops over the following eighteen months, he began slowing his artistic process down and breaking up his visual language into its discrete elements: form, colour, scale and story. Rather than trying as he had done previously to fit three and four ‘Dreamings’ on the one canvas, he decided to minimize his work and paint only the ‘trademarks’ of the story. Encouraged to continue in this vein he completed the first of his commissioned expressionist paintings at Papunya by reducing previously complex dreaming maps down into iconic logos and scaling them up. This literally breathed new life into his work and, following several more experimental painting and drawing workshops at Papunya, he began traveling to Brisbane three or four times a year to work at Campfire Studios. Through this collaboration Nelson has launched into a highly expressionistic genre, his minimalist surfaces embellished with singular, rapidly painted, calligraphic-like motifs that resound with the power of their ancient origins. The meticulous dot has been replaced with vigorous gestures executed energetically and haptically on to the painted surface of his canvases. Though he was represented in the exhibition Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius with a rendition of his Five Dreamings executed in the formulaic style he adopted while painting for the company in 1984, the success of his more recent works created while functioning as an independent artist, was underscored when he won the prestigious Tattersall’s Landscape Prize in 2006 for his expressionist painting Big Rain. While Nelson, like many of his contemporaries, maintains that Aboriginal art cannot be fully appreciated without comprehending its underlying attachment to a particular place and meaning, these new works appear to transcend the parameters of western desert art and have come to represent an entirely new and meaningful dialogue between traditional Aboriginal and contemporary European Australian art.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Geissler, Marie, ‘Michael Nelson Jagamara’ in Craft Arts International, #67, 2006

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Johnson Vivien, Michael Jagamara Nelson, Craftsman House, Gordon and Breach International, Sydney