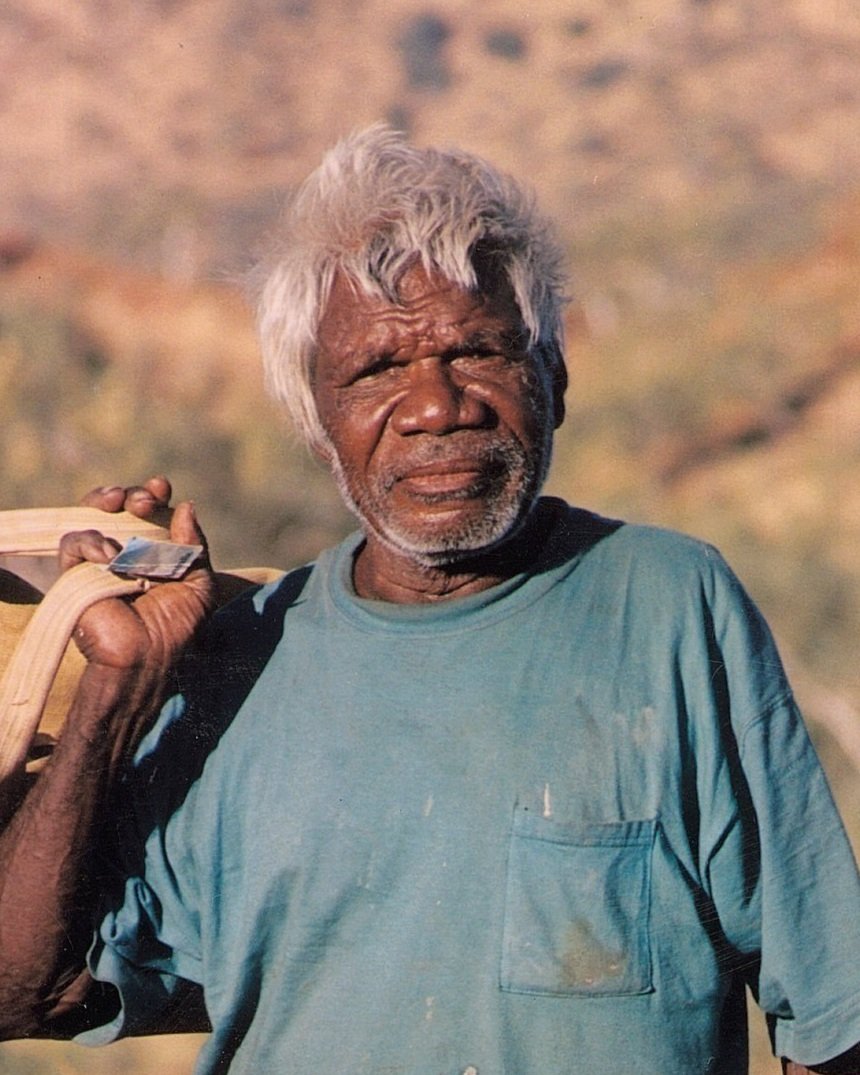

ROVER (JULAMA) THOMAS

BIOGRAPHY

Acclaimed as a cultural leader and the seminal figure in establishing the East Kimberley School, Rover Thomas is, according to almost every empirical measure, the most influential Aboriginal artist in the history of this movement. Yet, had he become an artist in his Walmatjarri-Kukaja traditional country, near Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route, his art would have doubtlessly developed along completely different lines, assuming he’d had the opportunity to paint at all. So remote was his birthplace that, had he not spent a lifetime of travel and finally settled in Gidja tribal country at Turkey Creek, hundreds of kilometres to the north, he would most likely have been drawn to the Warlayiriti artist’s cooperative at Balgo Hills when it was established in mid-1987. The Kukaja artists of Balgo Hills have much closer aesthetic ties to the Pintupi painters of Kintore and Kiwirrkurra in their use of representational symbols, such as circles, u-shapes and dotting drawn from low relief ceremonial ground sculpture than the Gija, whose primary influence is rock art and ceremonial body painting designs. Had he become an artist in his country, on the Canning Stock Route, it would have developed along completely different lines. Although he occasionally included figurative elements and topographical profiles in his paintings, Rover’s work is more familiarly characterized by an aerial perspective in common with Central and Western desert art. His most contemplative and sombre works draw the viewer into spacious planes of painterly applied and textured ochre. White or black dots serve only to create emphasis or to draw the eye along pathways of time and movement, following the forms of the land in which important events are encoded. In many of his works the predominant use of black conveys a startling, strangely emotional, intensity. Warm and earthy ochres, and a palpable sense of spirituality, invite the viewer on the one hand, to consider the unfolding of important events, while at the same time, purposefully sustain us in an ancient and timeless landscape.

Thomas began painting in his fifties, after spending forty years as a stockman. ‘I been all over, me,’ he said, when describing his intimate knowledge and involvement with the vast expanses of sparse desert and Kimberley terrain. He settled at Warmun in 1975, rather than returning to his own country deep in the desert, after political decisions caused large numbers of Aboriginal stockmen to be displaced from pastoral leases. Cyclone Tracy had cataclysmically laid waste to Darwin the previous Christmas and many Aborigines saw it as a sign that their culture and traditions needed strengthening. A powerful dream, involving the spirit of Rover’s dead aunt, inspired him to create a song and dance cycle that evolved into the Krill Krill ceremony. The spirit described the details of a journey that she had undertaken after her death, in the company of other spirit beings. In Rover’s re-visitation of that dream he too saw the places and the characters involved in the saga. At the end of the song cycle the travelling spirit looks from Wyndham, across the waters to the northeast, and witnesses the Rainbow Serpent’s vengeful destruction of the Territory capital.

The ceremonial reenactment of this dream took place for the first time in 1977 and was repeated at a number of locations in the East Kimberley region, in Arnhem Land, and further field through the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. During the ceremony painted boards, depicting the important sites and spirit beings, were carried on the shoulders of the participants. The boards used in the early ceremonies were created by Rover’s uncle and mentor, Paddy Jaminji, who was assisted by Jacko Dolmyn, Paddy Mosquito, Rover, and others.

In 1980 the Warmun community was still small and populated by a core of older Gija people. Rover himself did not paint as an individual until 1981. There were very few private galleries that specialised in Aboriginal art at the time. The Federal Government’s marketing company, Traditional Aboriginal Arts (Aboriginal Arts Australia), had galleries in most state capitals, including Perth, where Mary Macha, who had been a project officer with the W.A. Native Welfare Department since 1971, ran the company gallery. Paddy Jaminji had been the only person carving artefacts for sale during Macha’s field trips to Warmun throughout the 1970s. With assistance from Don McLeod, a field officer for the Department of Employment based in Kununurra, Paddy’s artefacts, including carved owls and ochre decorated boomerangs, made their way to her down south where they could be sold. In 1981 Mary Macha travelled to Turkey Creek with Mcleod on a field trip and saw Jaminji’s Krill Krill boards for the first time. These original boards, made only for the corroboree, were painted in earth pigments on housing debris, pieces of formica, wall panelling and wood from old packing cases. Despite originally refusing to sell boards to her, as they were used repeatedly in the Krill Krill ceremony and the board was difficult to replace, Jaminji later sold three shipments of paintings to Macha after she agreed to send good boards for him to paint on in future. Another frequent visitor to the community, and purchaser of artworks, from that time onward was Neil McLeod who began working on the first of more than 60 natural history books. Macha, McLeod and others relied on assistance from the Turkey Creek administrator, Remus Rauba, in order to arrange communication with the artists in the absence of phones and for the shipment of paintings out of the community.

In 1983 Macha left Aboriginal Arts Australia frustrated at their insistence on centralised buying and accounting from its Sydney headquarters, and decided to become an independent agent and consultant, representing Rover Thomas, Paddy Jaminji and other Western Australian Aboriginal artists. She remembered fondly Rover emerging from of a crowd at Warmun during her previous visit and, announcing himself to her, stated ‘Rover Thomas, I want to paint’. As a now independent dealer, she decided to support Thomas and Jaminjii and brought them down to Perth in 1984 and on a number of subsequent occasions to paint at her home in Subiaco where she made her garage into a studio.

Rover’s lead was soon followed by others and sparked a spiritual and cultural revival within the community, gradually expanding its influence and establishing the distinctive East Kimberley painting style. Other than Macha, McLeod and, for a short time in the mid-1980’s Chips MacInolty at Mimi Arts and Crafts in Katherine, the emerging art developed without assistance. In 1986, following a report written by Joel Smoker, the Kimberley Law and Culture Centre established Waringarri Aboriginal Art in Kununurra and Goolarabooloo Arts in Broome to help market the art of the region. While his public profile and reputation grew and his work gained wider commercial exposure through Waringarri’s exhibitions, Rover, and other artists, including George Mung Mung and Jack Britten, painted works of art from the mid-1980’s for anyone who turned up in the community and could be persuaded to part with their money. This included workers and advisers to the nascent Argyle Diamond Mine, government bureaucrats, casual visitors and dealers. Exhibitions organized by the Art Gallery of Western Australia and the National Gallery of Australia followed, and culminated in Rover’s selection as one of Australia’s two representatives at the Venice Biennale in 1990. These events, as well as his recognition on winning the John McCaughey prize, all increased his national and international prominence and generated the ever-growing number of agents and galleries who sought to represent him.

In 1995 Rover and members of his extended family travelled with Kevin Kelly, the manager of Warringari Arts, back to his birthplace on the Canning Stock Route, inspiring an impressive body of work. During the following year Peter Harrison of Kimberley Art Gallery and Neil McLeod took Rover Thomas and Freddy Timms to Melbourne. They lived with McLeod and painted daily in his studio in the Dandenongs. McLeod, a close friend and associate of Lin Onus, whose own studio was less than a kilometre away, hosted Thomas and Timms providing the support they required to produce a large body of work. These works were sold through Kimberley Art in Melbourne, Utopia Art in Sydney, Fireworks Gallery in Brisbane, and a number of other outlets, as well as to a band of dealers and private collectors who gathered around the artists during their time working in this studio environment. Upon their return to Turkey Creek, with advice from Peter Harrison, Dave Rock, the Warmun administrator introduced a scale of payments for each artist to counter exploitative payments by dealers who would turn up at the pensioner unit to commission artists and purchase works. Coo-ee Aboriginal Art ran two printmaking workshops in the community in the late 1990s and Rover Thomas, along with other important male and female artists including Queenie McKenzie and Jack Britten created acetates, plaster engravings, and linocut prints that were editioned by Studio One in Canberra during the following year. During the workshops many of their children made prints, while being mentored by the older artist’s. At the time the unfunded art centre was run by Maxine Taylor, who had been appointed by the Warmun Council. Referred to as Warmun Traditional Artists while under her management, it acted as the art centre in the community until 1998 when Kevin Kelly, instigated its incorporation. With a proper constitution and financial accountability, the growing art community at Turkey Creek was finally serviced by an ‘official’ art centre almost two decades after the first paintings were produced by artists who had already achieved international recognition.

In his final years, Rover worked for all of these organizations and, after Maxine Taylor left Warmun, he often visited her and painted at her home in Wyndham, where she had first met him. At this stage of his life, he referred to Taylor fondly as Nyumun (auntie), just as he did to Macha, who he began working with 20 years earlier.

Rover Thomas died on April 11, 1998 and was posthumously awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Western Australia. The power of his work was reflected in the attention it commanded from the beginning of his 15-year career. Since first exhibiting in 1987 there has been a constant demand for his paintings, which are now represented in all major galleries in Australia. He is recognized as the major figure in contemporary Australian Aboriginal art. His legacy is a substantial body of significant paintings that provide an enduring, unique, insight into the numinous landscape of the Kimberley region and the human relationships and events that have become part of its history.

*The Government marketing Company began under different names in different places and throughout its 16-year operations changed its name and identity several times eventually becoming Aboriginal Arts Australia.

**Neil McLeod and Don McLeod are not related

©Adrian Newstead

References

Caruana, W, 2001. Rover Thomas; ‘who’s that bugger who paints like me?’ World of Antiques and Art, no.62, Dec-June 2001-202:41-45.

McCulloch, S, 1999. Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Allen and Unwin.

Thomas, R, 1994. Roads Cross; The Paintings of Rover Thomas, National Gallery of Australia.

Holmes a Court Gallery, Rover Thomas, I want To Paint, Heytsbury P/L, 2003, catalogue of the Touring Exhibition

Luke Taylor, Painting the Land Story, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 1999

Anne Marie Brody, Stories, Eleven Aboriginal Artists, Eleven Aboriginal Artists, Works from the Holmes a Court Collection, Craftsman House, Sydney 1997