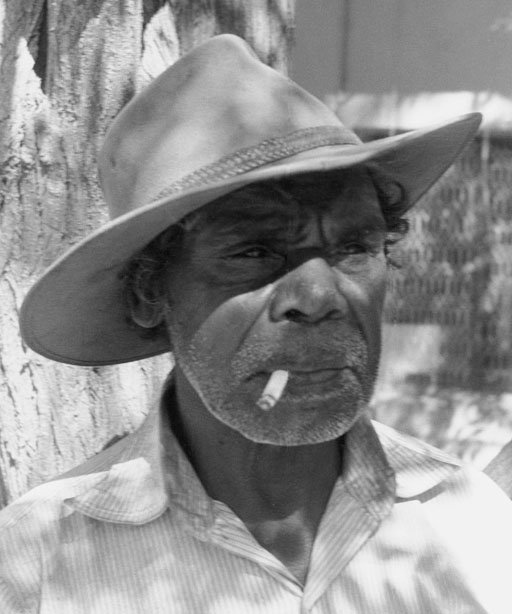

TIM LEURA TJAPALTJARRI

BIOGRAPHY

Flinders University Art Museum Collection.

Photo: Professor JVS Megaw

Before settling with his wife Daisy and their six children at Papunya in the early 1950’s, Tim Leura grew up and worked around Napperby and nearby cattle stations that had taken over his traditional tribal lands north-west of Alice Springs. Working for white people gave him a command of English as well as some familiarity with European ways, but tribal traditions were also maintained in this area and Leura was steeped in ancient lore. Along with his younger ‘brother’, Clifford Possum, he was acclaimed for his wooden carvings of snakes and goannas prior joining in the early artistic endeavours at Papunya.

Despite his initial reservations, Leura approached Bardon and became one of the four founding members of the western desert art movement. He was reportedly ‘ someone you sensed had thought a lot, and deeply ‘ (Wolseley, 2000, 377), and once he made a wholehearted commitment, became invaluable to Bardon as friend, assistant, and interpreter. Bardon wrote of him as ‘ A most gentle and endearing man…he was my dearest and closest friend in the Western Desert ‘ (Bardon, 2004, 89). Through the trials and tribulations of the art movement’s exuberant though fragile beginnings, Leura enabled the necessary dialogue to develop between Bardon and ‘the painting men’ and then later with interested outsiders. He was noted as having enlisted Clifford Possum, himself a renowned wood carver at the time, to the painting group. As the group grew, the men would often burst out in laughter at Bardon’s efforts to understand their explanations of paintings or his attempts to discuss visual aspects of their work, sometimes ‘ through relays of translations ‘. Yet Bardon recalls, Leura could always come up with a story that was comprehensible and acceptable to all.

In the process of acting as interpreter between artists and Bardon, Tim Leura also began developing his own distinctive painting style, which, more than any of his contemporaries, showed a willingness to engage with a cross-cultural sensibility. His concern to straddle the cultural divide, which impelled him to become a leading figure in Aboriginal art, was also the source of a deep melancholy, often discernable in his painting. Sitting in his own corner of the painting room with his board across his knees, Leura initially followed the ordered and symmetrical style that typified his Anmatyerre Arrernte tribal group and which proved appealing to buyers. He was drawn to subdued tones, mixing colours, dotting on to wet grounds, and blending outlines so that shapes would often run into each other. With great subtlety, he would include stylised animal, plant or skeletal human figures without disturbing his partiality for balance and clarity of design. Bardon strove to curb the group’s raw enthusiasm enough to slow their working procedures down and allow technical proficiency and stylistic innovations to develop. In Leura’s case this was to yield a creative departure from strict topographical and totemic mapping towards more painterly experimentation. He developed a remarkable elegance of tracery and filigree effects that eddied beneath and between the surface dotting, thereby creating a depth of suggested, though camouflaged, meaning. The style he developed was in keeping with the move to secularise the sacred Dreaming stories so that non-tribal outsiders could view them.

In his quietly authoritative manner, Tim Leura maintained a considered discretion in imparting traditional knowledge. He anguished over the loss and the humiliation his people had suffered yet at the same time he recognized that the eternal stories of his Dreaming must be kept alive and passed on to the new generations. Promoting awareness of his ancient cultural heritage seemed the best remedy for its threatened dissolution. Following the establishment of the Aboriginal Arts Board by the newly elected Labour government in 1972, Leura participated in a successful delegation to Sydney to secure funds for the emerging Papunya Tula enterprise. (Myers, p. 239)

While today Clifford Possum is the better known of the two ‘brothers’ Tim Leura is recognised as having been Possum’s spiritual mentor and instrumental in the development of Possum’s talent and technique. In the mid 70’s they collaborated on a series of monumental paintings incorporating several Dreaming stories in a map-like configuration. These works are regarded as being among the most significant in Aboriginal art. One of these, an 8.2 metre work on canvas, ‘Warlugulong’ (1976) was exhibited in the 1981 Australian Perspecta and is in the collection of the Art Gallery of NSW. Another collaborative work, ‘Napperby Spirit Dreaming’, was the principal painting in the landmark Asia Society, ‘Dreamings’ exhibition (1988-1989) and is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. In this magnificent seven-metre masterpiece produced in 1980, Clifford Possum and Tim Leura depart from a group tribal vision tethered to country and tradition, and reveal a subjective gathering of their own life history. Contained areas or ‘windows’ depict the Dreaming totems that sustained their life while a classic journey line runs through them, passing a skeletal spirit figure who waits and watches beside three resting spears. The somber, dappled surface reflects the deeply felt memory of Leura’s birthplace, recreating qualities of the landscape: leaves, smoke and grass, sand and earth imprinted with tracks and footprints. Clifford Possum’s crisp traveling line and central row of circles, contrasts with Leura’s meandering mode of building atmosphere through the disolution of solid form. He evokes a sense of the numinous, appealing to an aesthetic sense that transcends the arrangements of earthly existence. Often read as a painting in which ‘ death is dramatically prefigured ‘ (Corbally Stourton, 1996, p147), Leura became ill not long after finishing it and wandered lost and disoriented for a time before sadly dying in hospital of a brain tumor, his prolific career and unique perspective prematurely cut short. This painting, hanging in the National Gallery of Victoria, is a testament to Tim Leura’s far-reaching vision open to both the world of eternal stories, and to their sometimes difficult grounding in the circumstances of an individual life.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Corbally Stourton, Patrick, Songlines and Dreamings Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Painting, Lund Humphries Publishers, London, 1996.

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya, A Place Made After the Story, The Miegunyah Press, Australia, 2004.

Bardon, Geoffrey, Papunya Tula, Art of the Western Desert, Penguin Books Australia, 1991.

Johnson, V. Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert, Craftsman House. 1994.

Kreczmanski, J.B. & Birnberg, M. Aboriginal Artists Dictionary of Biographies, Central, Western Desert and Kimberly Region, JB Publications SA 2004.

Myers, Fred, R., “In Sacred Trust, Building the Papunya Tula Market” in Papunya Tula, Genius and Genesis, edited by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink. Art Gallery of NSW, Australia.

Perkins, P. & Fink, P. (Eds) Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, AGNSW 2002.

Wolseley, John, “Rock Wallaby Dreaming”, in Art and Australia, volume 37,#3, 2000.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008