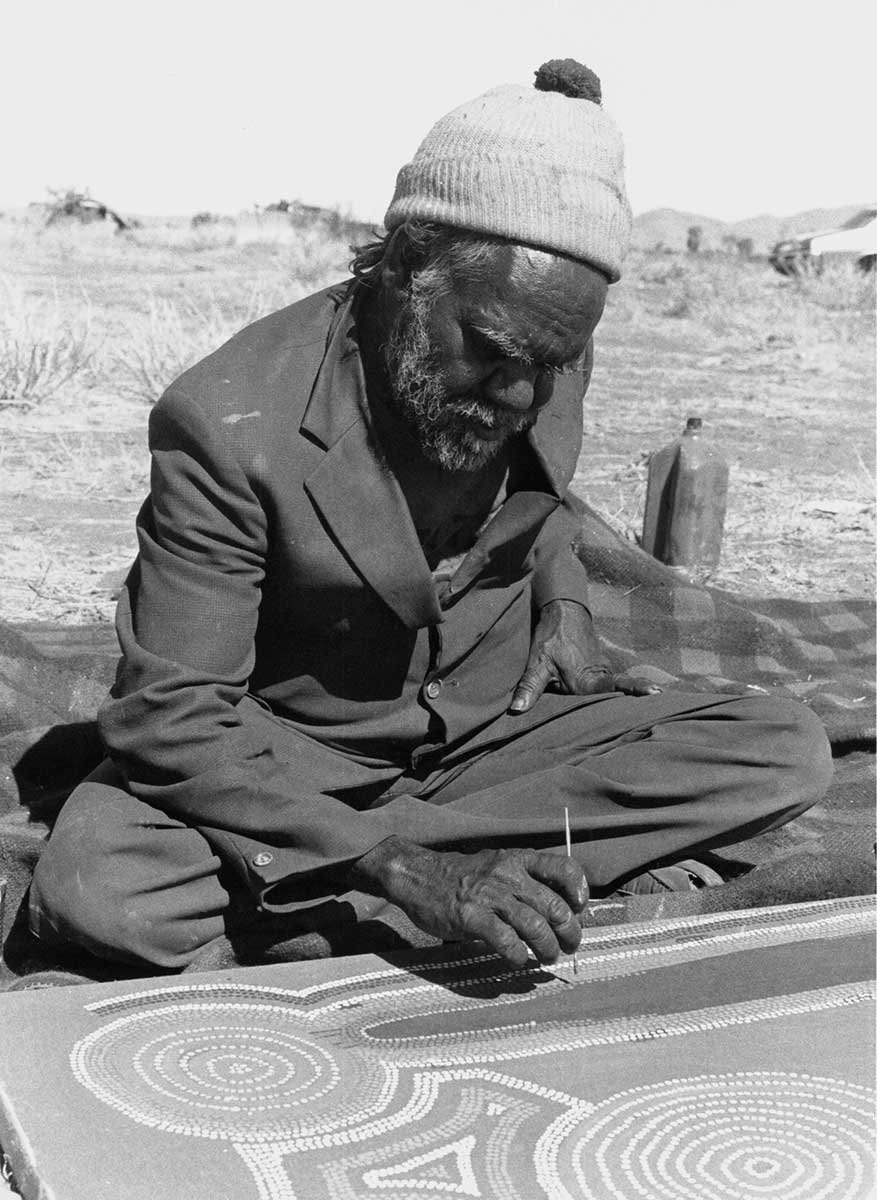

UTA UTA TJANGALA

BIOGRAPHY

Uta Uta’s painting career and reputation is closely aligned to the artistic renaissance that began at Papunya in in 1971. He was a founding member of the painting men, inspired other Pintubi tribesmen, and becoming one of the most senior and influential painters amongst the group.

Born in Western Australia in Drovers Hills, he made the epic journey to Haasts Bluff with his family during the severe drought of the mid to late 1950’s in the company of Charlie Tarawa. Two years later, after returning to his homelands, he made the journey once more with Timmy Payungka and Pinta Pinta and their families.

Employed as a gardener at the Papunya school Uta Uta, then in his 40’s, became one of the original group drawing and painting on composition board with encouragement from art teacher Geoff Bardon. Supplying paints to Uta Uta and his gathering group of enthusiastic friends, Bardon suggested the men use their existing cultural symbols to depict their Dreamings and links to the land. The Pintubi men, having been pushed from their traditional homelands by government policy and European development, painted under a bough shelter behind the camp, “pouring into their work their acute longing for the places depicted, …and chanting the song cycles that told the stories of the designs as they worked.” ( Johnson p190) These early works however, aroused strong protest within Aboriginal communities when first exhibited in Alice Springs in 1974 because of the disclosure of secret and sacred knowledge. A period of experimentation followed, resulting in the development of a symbolic language of classic ideograms and the characteristic dot covered areas that veil sacred elements from the uninitiated. The large, tribally mixed population of Papunya intensified the interaction, and under the influence of artists like Uta Uta, the painting group was able to break through the political and cultural constraints toward a safer stylistic conformity, thereby preparing the way for personal and distinctive styles to emerge. Uta Uta in particular with his exciting and charismatic personality as well as his bold and dynamic style played a vital role in these developments. Bardon recalled many years later, “Everything that came from him was genuine.” (Bardon 2004 p70)

Uta Uta’s 1971 and 1972 pantings generally featured major story elements with only the barest dotted in-fill within the iconography and small sections of the background. The aesthetic balance and harmony of these works is derived through colour and weight rather than by a geometric division of the painted surface. The rather crude dotting and line work of these early paintings on board embues them with an energy and power that is less apparent in his later more technically proficient works. His paintings are far stronger and more powerful when the clean unadorned background remains, unlike paintings by his contemporary Kaapa, whose early works became more aesthetically appealing as he began to in-fill the background.

In developing a style that censored the more secret and sacred content in his painting, Uta Uta added more dot-work as the years went by. He painted more Tingari sites completely surrounded by neat dots that became less and less detailed. Despite his advancing age during the late 1970’s he continued to paint as he spent increasing time at outstations west of Papunya and, at the beginning of the 1980’s he completed what was to become one of the most important and revered works of the entire western desert art movement. Yumari, 1981, possibly his largest and most significant painting, reveals the mythical Tingari ancestors traveling across vast stretches of country as they create sites and institute rituals. Yumari is a rocky outcrop in his home country and the key ceremonial site of the area. Story elements and natural features blend seamlessly into a beautifully balanced geometry of concentric circles and connecting lines that enclose a central, abstracted figure. His body continues rather than interrupts the intense, minutely dotted background configurations, yet still holds the central focus. The work is characterised by the sinuous movement of converging regular and irregular shapes, accentuated by outlining white dots. The predominant use of an earthy red alongside vivid yellow ochre, further emphasizes the assertive quality in this cohesive and powerful statement of Aboriginal tradition. The work was exhibited at the XVIII Bienal de Sao Paulo in 1983 and is now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia.

While painting Yumari, important discussions were taking place at Papunya concerning the move back to the Pintubi homelands at Kintore. Land rights legislation during the 1970’s returned ownership of the land to its traditional owners and Uta Uta was a strong advocate for resettlement. The community art advisor had given Uta Uta the large stretched canvass and soon noticed, with some anxiety, that he was sitting cross-legged in the middle of it, singing determinedly as he painted. Eleven of his kinfolk including Anatjari Tjampitjinpa, Charlie Tjapangati and Yala Yala Gibbs later joined him to assist with the dotted infill and all managed to balance on the wooden struts as they worked and talked excitedly about the practicalities and possibilities of the Kintore outstations. (Kimber, p215) As a direct consequence of this and other art sales, income was generated that enabled Uta Uta to be amongst the first to set himself up with his family on a small outstation west of Kintore, thereby inspiring others to follow his example. (Williams, p227).

The painting movement, given impetus through Uta Uta’s outspoken confidence in his people, had re-ignited a growing pride in their ancient heritage and a communicable enthusiasm for their Dreaming stories. It provided a meaningful world-view that could be passed on to the younger generations, giving them both inner spiritual and outer material resources for their own self-determination.

The Western Desert art movement burgeoned, spreading along the lines of kinship and family that ultimately connect all desert communities, allowing an important dialogue to occur between past tradition and the demands of the present. Many of his offspring and immediate family became artists that would carry the baton of desert painting in to the next decade and beyond. They included his wife Walangkura Napanangka and their five children including Shorty Jackson who often assisted his father on the dotted backgrounds of his late career works. Although Uta Uta died in 1990, his work continues as a strong voice within the ongoing dialogue of western desert art and, unlike many of his contemporaries who began working with Geoff Bardon, many of his late career works are considered of equal or greater importance than his early boards. This was amply demonstrated when in 1985 Uta Uta won the National Aboriginal Art Award at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Anderson C., and Dussart F., “Dreamings in Acrylic: Western Desert Art” in Dreamings, The Art of Aboriginal Australia, edited by Peter Sutton, Penguin Books Australia, 1988.

Bardon, G., and Bardon, J., “Lives of the Painters” in Papunya :a place made after the story; the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic., 2004.

Johnson, Vivien, “Seeing is Believing, A brief history of Papunya Tula Artists” in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, edited by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Art Gallery of NSW, Australia,

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Kimber, R.G., “Central, Western, Southern and Northern Desert” in Aratjara, Art of the first Australians, Germany 1993.

Williams, Daphne, “Company Business” in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, edited by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Art Gallery of NSW, Australia, 2000.