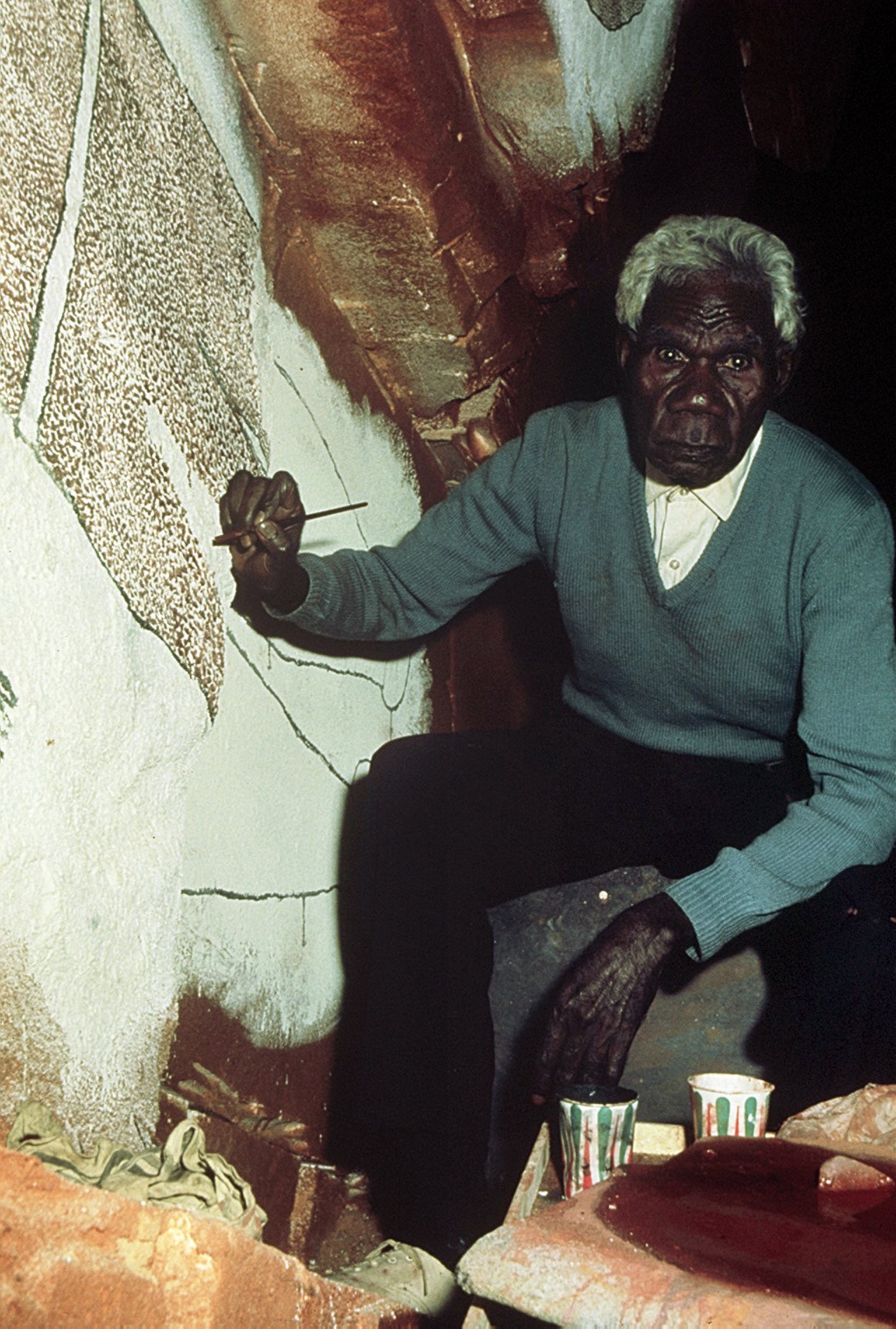

WATTIE KARRUWARA

BIOGRAPHY

Wattie Karruwara was born in the Hunter River basin in the far north west of Western Australia c1910. In 1921 while still young, two shipwrecked sailors stole a canoe from a clansman and, in an attempt to cross the Hunter River, became swamped. On their return to shore, the owner of the canoe speared and killed them, and as a consequence the police detained two men and four women, of whom Wattie was one. After a period in Wyndam jail and a trial in Perth, Wattie Karruwara was eventually released as a minor, set free in the alien surroundings of Perth. It took him some twenty years to return to Broome and his home at Mowanjum, during which he worked with the police as a tracker in the gold fields of Western Australia.

In Mowanjum, Wattie lived with his uncle Micky Bungkuni a senior Wunambal elder who painted infrequently, and under his guidance, Wattie also began painting works. A few of these have been found over the years, through various anthropologists who studied in the Kimberley area at that time. The earliest record of one of his paintings is a work titled ‘Wandjina Man with long neck,’ which was collected by anthropologist Norman Tindale in 1953. A number of Wattie’s works were donated to the University of Western Australia in the 1960s by linguist Peter Lucich, while Wandjina paintings created during the 1970s for Helen Groger Wurm are now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia.

Wattie’s Wandjina figures fall within the traditional genre of the region. The Wandjina are unique to the rock art of the Kimberley. They are said to have lain down in the caves and turned into a painting after their activities on earth (Ryan 1993: 11). These spirit ancestors usually appear with a large face and dark eyes, but with the mouth absent. The Wandjina takes many forms according to the exact location and tribal group that are its custodians. Images can usually be identified across artists as they have strong individual traits. Wattie Karruwara and Charlie Numbulmoore, were among the first artists to emerge as individual artistic identities prior to the 1970s. Karuwara’s Wandjina’s are distinctive with long rays emanating vertically from the headdress, small eyes, nose, and delicate hands and feet.

However Wattie is most famous for a series of watercolours, quite different from these Wandjina paintings, and his occasional boab nut carvings. His works on paper were the result of a friendship developed between the artist and American anthropologist John McCaffrey who, in the early 1960’s, singled out Wattie’s genius and provided him with small flat painting surfaces. Initially these took the form of portable barks, which McCaffrey had flown from Arnhem Land through Professor Roland Berndt, as bark painting was not a Kimberley tradition. However the difficulty in obtaining the bark led the anthropologist to look for a simpler medium and, in Perth, he purchased the best quality paper and Windsor and Newton watercolour paints (Flynn 2003). The results were astounding and McCaffrey noted that Wattie painted ‘sometimes up to eight hours straight, in a trance like state with eyes open” (cited in Flynn 2003: 10). Karruwara completed the series at the Derby Leprosarium, after being diagnosed with leprosy. His friend McCaffrey “spoke sadly of his leave-taking of Wattie, and was pleased to learn in 1997… that Wattie had later been released, and had lived until 1983,” (Flynn 2003: 10). In all, more than 38 watercolours resulted from their exchange, the beauty of which, resides in the naive charm of the colourful semi-naturalistic depictions of the flora and fauna of his country.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Akerman, Kim. July 2003, Wattie Karruwara, Sotheby’s Catalogue, Sydney.

Flynn, Kate, July 2003, Biographical Notes on John McCaffrey,’ Sotheby’s Catalogue, Sydney.

Ryan, J., 1993, Images of Power, Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, exhib, cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.