ABIE JUMBYINMBA TJANGALA

BIOGRAPHY

Born at Thompson’s Rockhole in the Tanami Desert, Abie Jangala was initiated in to Warlpiri Law and inherited his father’s responsibility for the essential Rainmaking and Water Dreamings of this vast and arid desert area. The Warlpiri were still nomadic hunter-gatherers when forced by drought to gather around the encroaching European settlements in the Tanami and Western Deserts. Abie began working at the Granites copper mines, where he first learnt English and became familiar with European ways. Despite the necessity of regular visits to his sacred sites for ceremonial purposes and for further instruction from his father, Abie was trucked off to Alice Springs to build army barracks, roads and an airstrip when the war broke out at the beginning of the 1940’s. By the time he returned several years later, his family had been settled at Yuendumu, an overcrowded and somewhat chaotic government settlement on the edge of the Tanami Desert. Eighteen months later in 1948, Abie was trucked off once more; this time, to build a new settlement at Hooker Creek on Gurinji land, hundreds of miles from his own country.While many of his people, unhappy with being so distant from their Dreaming sites, walked back to familiar territory, Abie stayed on and the small community of Lajamanu slowly grew. New children were being born and in this new ‘country’ they become responsible for new Dreamings, which required observance. However Abie was regularly called back to his own country. His father died and ceremonial seniority was passed to him. Thus he became the ceremonial boss of the Water, Rain, Cloud and Thunder Dreamings, the most senior ‘rain man’ in the northern Tanami region.

On hearing of the growing popularity of painting amongst the Pintupi and other groups in the Western Desert, the Warlpiri men of Lajamanu and Yuendumu were initially highly suspicious. A number of community elders considered painting to be a shameful exposure of secret and sacred Warlpiri knowledge. It was during this time that Abie was included in a group of twelve Warlpiri men who traveled to Paris in 1983 to create a traditional sand-painting and perform corroboree at the Musee d’Art Moderne. Their traditional designs had only ever been painted on skin and etched in sand and the group were still strongly opposed to committing them to any permanent medium. ‘The permanence of these designs is in our minds,’ they stated publicly, ‘we are forever renewing and recreating these traditions in our ceremonies’ (Jangala 1977: 103). The group’s visit to London, the Unites States and the capital cities of Australia was their introduction to the contemporary art world and generated a huge level of interest and awareness.

Three years later the Warlpiri position had changed and an adult education course run by John Quinn introduced western art materials and methods at the local school. Abie Jangala played a key role in negotiating a middle path through the conflicting points of view amongst elders reluctant to engage in painting. However, as artistic activity strengthened, a much-needed source of income was established for the community. The establishment of Warlukurlangu Artists at Yuendumu had already shown how permanent records of traditional designs provided a means of preserving and maintaining the culture, while the stunning success of artists who initially lived at Papunya and had used money earned from painting to re-establish their links to country closer to Lake MacKay, gave promise of financial rewards. The women of Lajamanu in particular were anxious to see their children provided with some source of spiritual grounding in the face of so many modern influences and distractions. However, Lajamanu’s isolation, due to its great distance from the urban art centres and the difficulty of communication with the outside world, slowed the public emergence of Lajamanu art significantly. As late as 1989, there were still no telephones to connect the inhabitants of the community with the outside world. However, the arrival of a satellite dish from Yuendumu resulted in a teleconference link up with the director of Coo-ee Gallery in Sydney, his curator Christine Watson and Allan Warrie of the Aboriginal Arts Board, during which Abie and other Lajamanu artists presented their work and an exhibition was arranged for the following year. In that same year, Perth gallery director Sharon Monty flew into the small community and, impressed by Abie Jangala’s ‘awesome and imposing presence,’ his wonderful sense of humour, his patience, and his willingness to explain the content of his paintings, she began to represent him in Western Australia. Thus he became the first artist from Lajamanu to have solo exhibitions and a painting career that led the way for other artists from there. By 1991 Judith Ryan had published a book ‘Paint Up Big’ on the new Warlpiri art movement for the National Gallery of Victoria and the following year Gallerie Boudin Lebon in Paris exhibited their work curated by the anthropologist Barbara Glowszewski. In the early 1990’s, due to poor administration, Lajamanu lost the funding that would have enabled it to maintain a fully functioning art centre. Lava Watts assisted the artists voluntarily and with the closure of Sharon Monty’s gallery in Perth, she helped to forge a representative relationship for Abie Jangala with Coo-ee Aboriginal Art Gallery in Sydney. This relationship lasted until Abie’s death, including the short periods during which the art centre was resurrected. Through this relationship Abie was provided with art materials and also produced a large body of works in the print medium.

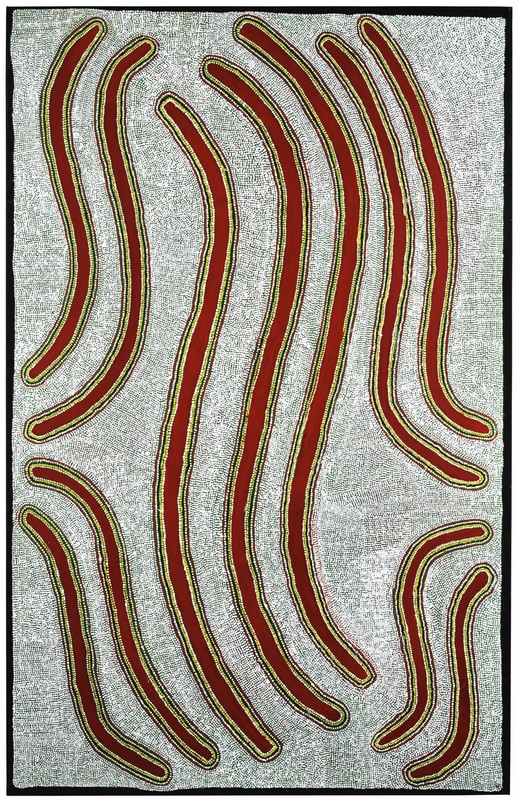

From the outset Abie Jangala’s paintings were unique recreations of the iconography that pertained to rain making ceremonies and the reverence in which Dreamings associated with the Rainbow Men are held amongst Warlpiri people. His early works were created on a deep thalo green or black ground with the stark symbols specifically representing rainbows, lightning, clouds, waterholes and frogs, composed in much the same way as they are etched in relief on the body of rainmakers when covered in kapok or feather down for ceremony. Abie typically painted these powerful symbols, which are also recreated in ceremonial ground constructions, in solid black or red, outlined in single alternate bands of bright yellow, green and red dots, thereby emboldening the icons to evoke the shimmering and alluring effect of the Rainbow Men and their dramatic manifestation as natural climatic phenomena. This allure is imitated by the glint from pieces of broken mirror or shiny belt buckles worn and carried by men in ceremony; and the glistening skin of women covered in animal fat and red ochre. Typically these paintings are in-filled with compact white dots representing rain or fields of hailstones. At the height of his artistic powers Abie could apply these uniform white dots in such a way as to evoke the same meditative quality as that of the raked grounds of Zen meditation gardens. Abie once explained that he painted, ‘the proper paintings… they are from my father. He comes to me in dreams and tells me what to paint, and how paint it’.

As the composition of his paintings turned to more symbolic ways of depicting ancestral stories, the choice of colour emphasised their kuruwarri, to make them ‘really strong’ (Kleinert 2000: 611). While his early paintings were created in traditional earth colours that vibrated with contrast and intensity, he quickly moved toward high contrast by employing green and red in the textured ground and, towards the end of his life, paler shades of blue and mauve thereby creating more subtle gradations of light and dark. By this late stage in his painting the in-fill had lost its precise execution and resultant meditative quality, giving way to a blizzard of small interconnected, overlapping and melting white dots.

At the time of his death, despite his inability to paint, he worked on etching plates, a number of which were editioned posthumously. One of these, in which the white dotted field was embossed, was part of the landmark Yilpinji-Love Magic portfolio including prints by fifteen of the important senior Warlpiri and Kukatja artists in Lajamanu, Yuendumu and Balgo Hills.

Although Abie Jangala’s life spanned a period of momentous change and re-invention for the Warlpiri people of Australia’s remote Tanami Desert, his quiet determination to work constructively within imposed and often challenging constraints, saw him win acclaim during his lifetime as the greatest living Walpiri painter.