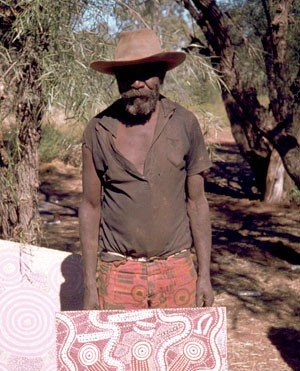

CHARLIE TJARURU TJUNGURRAYI

BIOGRAPHY

Photo: Graeme Marshall

Born west of the Kintore Ranges, in Pintupi country, Charlie Tjararu’s friendship with Europeans began early and continued to be instrumental throughout his life and career. He first encountered whitefellas as a youth and in his early teens lived for some time at haasts Bluff before returning with a prospecting party to his homeland. By the onset of the Second World War he had moved to Hermannsburg and worked for some time as a builder there and with the army at military camps around Adelaide.

In the 1950’s he moved with his family to live at Haast’s Bluff, near Papunya, but still traveled out into the desert to contact and take rations to his people, often liaising for the welfare patrols who sought to draw the various tribes of desert dwellers into the government settlements and assimilate them into the encroaching white society. From its very beginnings however, Papunya was a place of tribal tensions and government neglect, and the Pintupi strove to establish their own camps, removed from the ‘conflict and grog’ that threatened their tribal integrity. When the painting group began on the veranda of Geoff Bardon’s flat in 1971, Tjaruru enthusiastically applied himself realizing, along with the other men, that this was one way they could improve their situation. Ultimately they hoped to return to and set up independent outstations within their homelands.

An adventurous and energetic man, Tjaruru was a predominant figure in the Papunya community during the 1970’s. He was a founding member of Papunya Tula and became an important spokesman for the Pintupi due to his strong command of English, despite a number of the white people in the settlement characterizing him as ‘difficult’ or ‘bitter’ (Johnson V, 2008). Yet Bardon himself found him ‘accessible’ and of ‘quiet disposition and warm loyalty’ (Bardon G, 1979 p46). His versatility with language and European customs enabled him to guide and explain on both sides of the cultural divide, the financial and cultural transactions that were the basis of the fledgling art business. He was the eldest of the many Tjungurrayi skin ‘brothers’ that included Kingsley, Shorty Lungkata and Yala Yala as well as Don, George, Willy, Two Bob and Yumpululu who would follow them in to painting. As such, he took it upon himself to look after their interests. At the same time, he proved himself a prolific and talented painter, responding to criticism with a good-natured determination that saw through to the consolidation of the distinctive Pintupi style. His own work reflected this formal structuring, particularly his renditions of the Tingari creation myths, but at times he gave way to a more experimental flair. The vitality of his brushwork gave his works a characteristic textured surface that emphasized his attachment to solidity of form, and imparted a ‘vigorous presence’ to his paintings. Because of controversy surrounding the depiction of sacred subjects, Bardon suggested painting children’s stories that trace more general activities of traditional life such as food gathering. At the time it became a pathway to peace among the differing opinions as to what subjects and images were safe to reveal and Tjaruru helped to show the way forward with his vibrant Yam Dreaming, 1972. This painting was intended to teach young people where and how to find this valuable desert food. (Bardon, 2004) It was Tjaruru who suggested to Bardon in 1972 that the newly established company be called Papunya Tula. Literally meaning ‘a meeting place of brothers and cousins at the Honey Ant place’, the small hill that looked over the Papunya settlement. It seemed to satisfy everyone, pointing to a new business arrangement that acknowledged an Aboriginal conception of sociability and consultation. (Carter, 2000,p.249)

When Andrew Crocker came to Papunya as the new art advisor in 1981, a strong friendship developed between the entrepreneurial English man and Tjaruru who was, as described by Bardon, “by far the most accessible of the Pintupi painting men” (Bardon cited in Genesis and Genius, 2000. in biographies, p 293) Crocker significantly raised the profile and sales of Papunya Tula. He contacted wealthy people around Australia and overseas, encouraging their interest in the paintings and selling a sizeable collection to the Holmes a Court family. The company broke free from its dependence on annual government grant money and a wider group, including women, became involved in producing art works. (Kimber,2000, p.208) Crocker brought Tjaruru into the limelight, as a representative of the company but also as an artist in his own right. They traveled together to Europe, America and, in England, Tjaruru met with Queen Elizabeth the second. In 1987 he was afforded the first retrospective devoted to an Aboriginal artist, organised by Crocker, for the Orange City Festival, which later toured Australia. (Crocker,1987) Because of the complexity of his relationship to both his white friends and his own culture, Tjaruru was deeply affected by these experiences, so removed from the basic difficulties his people faced as they began their exodus back to Kintore. His authority and political position within the Pintupi community wavered somewhat, even though he remained confident of his own importance. (Myers,2002,p.78) There is no doubt however, that the growing economic and political value of painting which enabled the Pintupi to regain their beloved homelands and determine an independent and hopeful future, was greatly powered by the vitality and heartfelt persistence of Charlie Tjaruru. He did eventually return to live in his Pintupi country, 25 years after he left it by camel in 1956 aided by the money generated from his art sales. He and his wife Tatali Nangala who passed away shortly after her husband at the end of the 1990’s had 9 children although tragically 5 of these died before their parents. Charlie Tjaruru lived an eventful and extraordinary life. Today his art resides in collections around the world and testifies to a life rich in spirit, despite the often alien world, and personal sadness that he encountered.

© Adrian Newstead

References:

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya, A Place Made After the Story, Miegunyah Press, Australia, 2004.

Carter, Paul, “The Enigma of a Homeland Place” in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of NSW, 2000.

Crocker, A., Charlie Tjaruru Tjungurrayi: A retrospective 1970-1986, Orange Regional Gallery, orange City Council, NSW, 1987.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008

Kimber, R.G., “Recollections of Papunya Tula 1971-1980” in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of NSW, 2000.

Myers, F.R., Painting Culture, Duke University Press, USA, 2002.