CLIFFORD POSSUM TJAPALTJARRI

BIOGRAPHY

Clifford Possum was the first recognised star of the Western Desert art and one of Australia’s most distinguished painters of the late twentieth century. After his father, Tjatjiti Tjungurrayai, passed away during Clifford’s youth in the 1940s, his mother, Long Rose Nangala, settled at Jay Creek with her second husband, One Pound Jim Tjungurrayai. One Pound Jim, a legendary figure in Central Australia, acted as guide to early travellers and anthropologists and became the Aboriginal face of the centre after his portrait featured on the stamp used by the Australian postal service between 1950 and the introduction of decimal currency in 1966. It was under his tutelage, with that of other Tjungurrayai men that Clifford was initiated into manhood at Napperby Station. Yet it was from Tjatjiti’s country West of Mount Allan that Clifford inherited his famed Love Story and this, along with the Bush Fire Dreaming inherited from his mother’s country south of Yuendumu, became the major Dreamings he came to depict in his art.

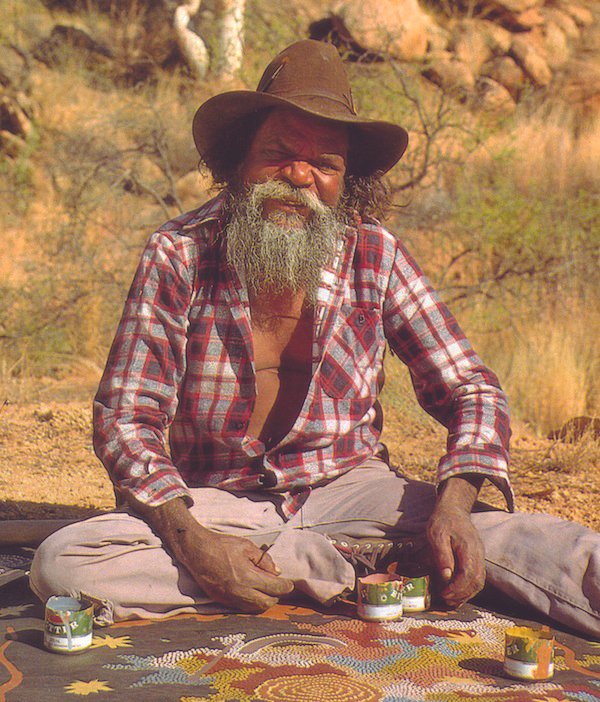

During his early days Possum worked with cattle at Glen Helen, Mount Allan, Mount Wedge, Napperby Station and Hamilton Downs. He began his artistic career at Glen Helen when he found that he earned more pay and lived under better conditions while producing carvings for the developing tourist market than he had as a stockman.

His carvings of wooden snakes and goannas, like those of his classificatory ‘brother’ Tim Leura, were renowned in Central Australia for their brilliant craftsmanship. Together they worked on the construction of the Papunya settlement in the early 1950s, joining Clifford’s first cousin Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, the son of Long Rose’s sister Margie Long. It was during this period that Clifford married Emily Nakamarra who became the mother of his four children, Daniel, Lionel, Gabriella, and Michelle. Tim Leura became a founding member of the Papunya Tula artists, Clifford Possum did not join the growing band of active painters working with art teacher Geoffrey Bardon until February 1972.

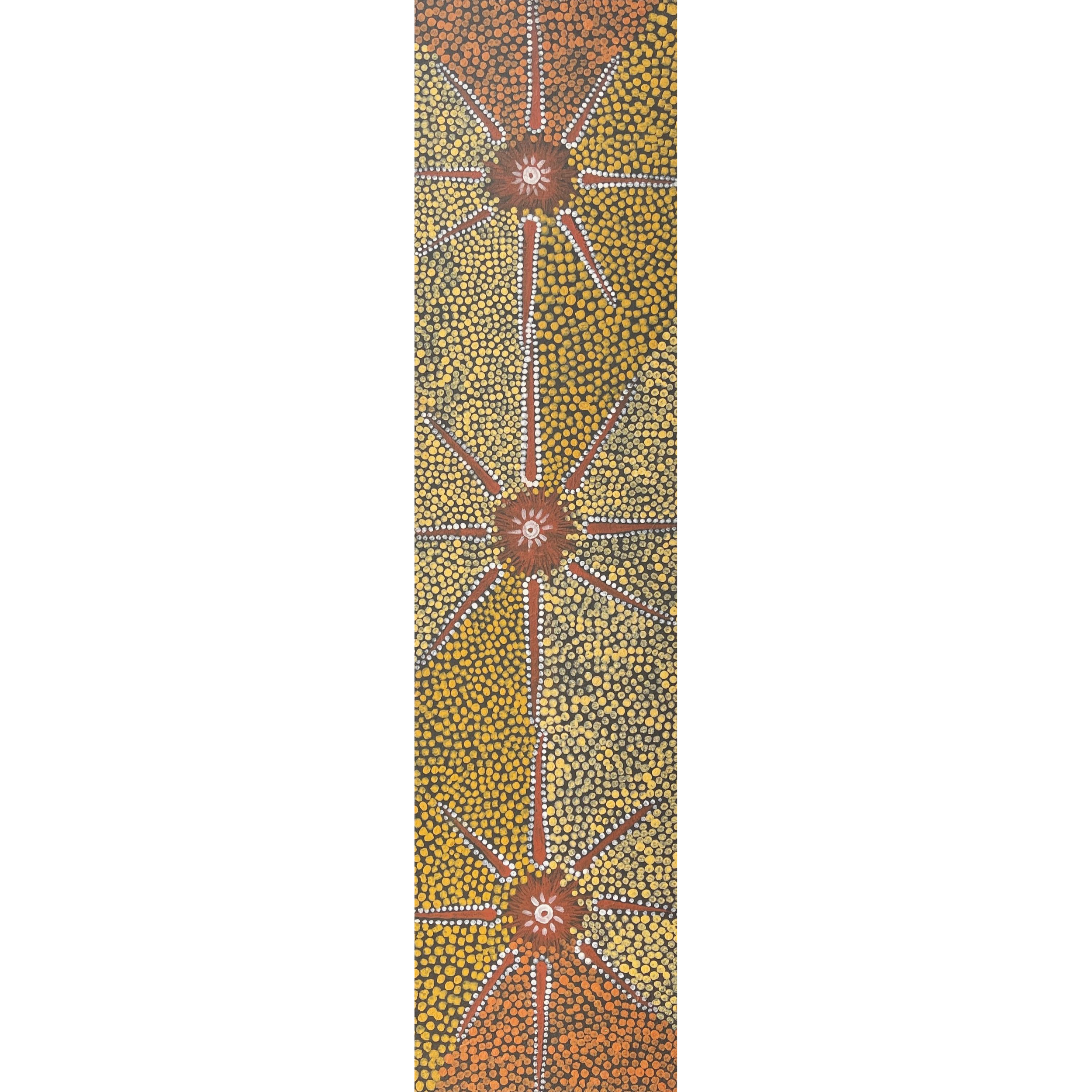

His unique artistic style developed rapidly and was characterised by its innovative use of spatial configuration beyond the more conventional Papunya idiom of dots, circles and lines. This inventiveness with space, perhaps derived from his skills in woodcarving prior to the Papunya movement, resulted in early paintings that conveyed a remarkable sense of atmosphere. These stood out from those of other Western and Central Desert artists, who were less preoccupied with evoking a psychological mood in their paintings. His small early career works, however, were a mere foretaste of the grandeur of the paintings he was to create, on an unprecedentedly massive scale, in the late 1970s. They have been described as ‘beautiful palimpsests’ of his extensive multiple Dreaming sites, seen from shifting viewpoints in space. Clifford’s works at this time enabled the ‘unfamiliar viewer to see these sites as a fusion of the abstract diagrams of ancestral passage in the traditional expressive forms of the Western Desert, with the maps of Europeans’ (Johnson 2003: 79), a form very familiar to the Western onlooker.

As he developed his art practice, Clifford introduced Western iconography and figurative imagery to convey certain elements in his narratives. This played a dual role in both making them more intelligible to western audiences, and allowing him to create imaginative compositions within the parameters of the ‘law’. Possum was acutely aware, as one of the founders of the desert paining movement, that to give away too much ancestral meaning could at that time have risked his life. He employed a set of his own invented, secular, non-traditional motifs in what would become a recurrent theme in his art, the ‘Man’s Love Story.’ This story is a story of the Tjungurrayai man who desired, against kinship rules, a Napangardi woman, and wooed her by spinning hair string while singing love songs. This and other works from the start of the 1980s onwards are characterised by a complex of designs rendered with modulated tone and broken colour. The fractured shaping of the in-filled fields of dots achieves an extraordinary visual effect, ‘flat but with a thin three-dimensional disguise’ (Bardon 2004: 82). It was only towards the end of Clifford’s life that there was a dramatic reduction in his palette. His most emblematic final works are bleak depictions in black and white; boys skeletal remains float starkly on unadorned backgrounds as if ethereally infused with the artist’s ‘own impending sense of death’ (Nicholls 2004: 24).

The retrospective of his work that toured extensively throughout Australia from 2002 included works spanning the artist’s 30 year career with the wonderful examples of his early smaller works of 1972-1973, and the dramatic skeletal sketches of the final years acting as the bookends to a great artistic adventure. While Clifford himself may have pointed to his private audience with Queen Elizabeth II as the highlight of his career, the low point was most likely his discovery of an exhibition full of fakes in Sydney in the late 1990s and the adverse publicity that this attracted.

Despite the fact that he was the only Papunya Tula artist honoured with a solo retrospective by a major institution by the beginning of the current millenium, he forsook his association with the organization almost entirely by the mid 1980s. He returned to his Anmatjerre homeland at Mount Allan and began selling his works directly to the government marketing company, Aboriginal Arts Australia, in Alice Springs. He also signed and passed off as his own many other works that had been produced by Michael Tommy, Brogus Tjapangarti and other countrymen in order to maximise their income.

In the late 1980s he produced a large body of works for John O’Laughlan who acted as his agent and travelled with him to his exhibition at Rebecca Hossack Gallery in London. Clifford worked for a time with disgraced dealer Chris Peacock in Adelaide whose company TOAC printed the logo ‘Bush Myths’ on the back of all canvases. Peacock worked with many artists who painted outside of the art centre system including Emily Kngwarreye. He was reported to have used stand over tactics and violent threats in forcing Possum to sign paintings that were not entirely his own. However the truth is elusive as sadly, by this time, Clifford was addicted to alcohol and gambling and was producing a large number of perfunctory minor works, signing paintings that he ‘owned’ but which he did not actually paint and others that were not entirely executed by his own hand.

Throughout the early 1990s he lived and travelled with his daughters Gabriella and Michelle and his son-in-law Heath Ramzan as well as others. He worked for a variety of dealers including, Michael Hollows at his Aboriginal Desert Dreaming Gallery, Peter Los in Alice Springs and Semon Deeb at Jinta Gallery in Sydney. He painted for Frank Mosmeri in Broadmeadow and Des Rogers in Sunbury on the outskirts of Melbourne, and Swiss collector Arnaud Serval, who seemed to share a good relationship with the artist and ensured the works he handled were entirely in Clifford’s own hand. No doubt there were a great many others, as Clifford was a born entrepreneur and was in constant need of money. For a time his affairs were managed by Joy Aitken who sold amongst the genuine paintings, individually painted by Clifford and his daughters, many collaborative works where the daughters assistance was never acknowledged. Leaving Aitken with a number of canvases in various states of completion it appears that out of desperation, given the financial difficulties involved in keeping the ‘Possum Shop’ going, she crossed the Rubicon and completed the dotting on some of these works herself.

Clifford’s career and standing reached its nadir when a solo exhibition organised for an important Sydney gallery in the late 1990s was exposed as being almost entirely composed of fakes. The works had been commissioned by the late Patrick Corbally Stoughton from Alice Springs based dealer John O’Laughlan who was found guilty of fraudulent involvement. When Clifford came down to view the exhibition he visited the Art Gallery of NSW and other institutions pointing out countless works purported to have been created by him but which he denied having painted.

In abandoning the communal identity of the Papunya movement in favour of personally negotiating with the dominant western mainstream, the motivation of his painting practice became blurred in favour of his fame as a personality. In this regard his life was not dissimilar to that of Albert Namatjira who died 40 years earlier, before the Papunya movement had even begun. Both began their lives in a creek bed, light years from the international art circles in which they would later move with such fearless assurance. Clifford was actually asked by Namatjira to continue in his footsteps (Johnson 2002: 243), although undoubtedly he did not mean that he should do it quite so literally.

Although physically unwell and with failing eyesight Clifford Possum lived throughout his final years in a loving relationship with Milanka Sullivan at Warrandyte in the hills outside of Melbourne and created many of his finest late career works in her care. Sullivan has continued to work since Clifford’s death in 2002 authenticating his paintings and uncovering suspect and fake works and writing a book that she maintains will re-establish Clifford’s reputation as Aboriginal Australia’s finest painter.

No life was written larger across the page of the Aboriginal Art Movement than that of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri. During a career, which lasted more than 30 years, he produced a number of masterpieces that will come to be seen by Australians as amongst the most important works created in this country’s artistic history. His inclusion in major national and international exhibitions and his presence in the literature rivals that of any other Australian Aboriginal artist. He received an order of Australia for his contribution to the Western Desert art movement, was chairmen of Papunya Tula in the late 1970s and early 1980s, had a private audience with Queen Elizabeth II in 1990, and was the first real Ambassador for Aboriginal art around the world. He was honoured posthumously by a solo retrospective by the Art Gallery of South Australia which toured state galleries and, moreover, was the subject of two books on his life and work written by Vivien Johnson, his long time friend and biographer.

©Adrian Newstead

Bibliography

Bardon, G. 2004. Papunya: A Place Made After the Story, The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement, Bardon, G & Bardon J (eds), The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University, Victoria.

Hill, P. May 8-9, 2004. ‘Spiritual Maps.’ Sydney Morning Herald, Spectrum,: 8-9.

Johnson, V. 2003. Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide.

Johnson, V. 2002.’Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri c. 1932 - 21 June 2002 Obituary.’ Art and Australia, v.40, no.2: 243-244

Lock-Weir, T. June-July-Aug 2003. ‘Clifford Possum, the divine navigator,’ Art and Australia, v.40, no.4: (602)-609

McNamara, A. Summer 2004/05. ‘No Two Ways About It: On The Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarrii Retrospective.’ Eyeline no. 56: 13-17