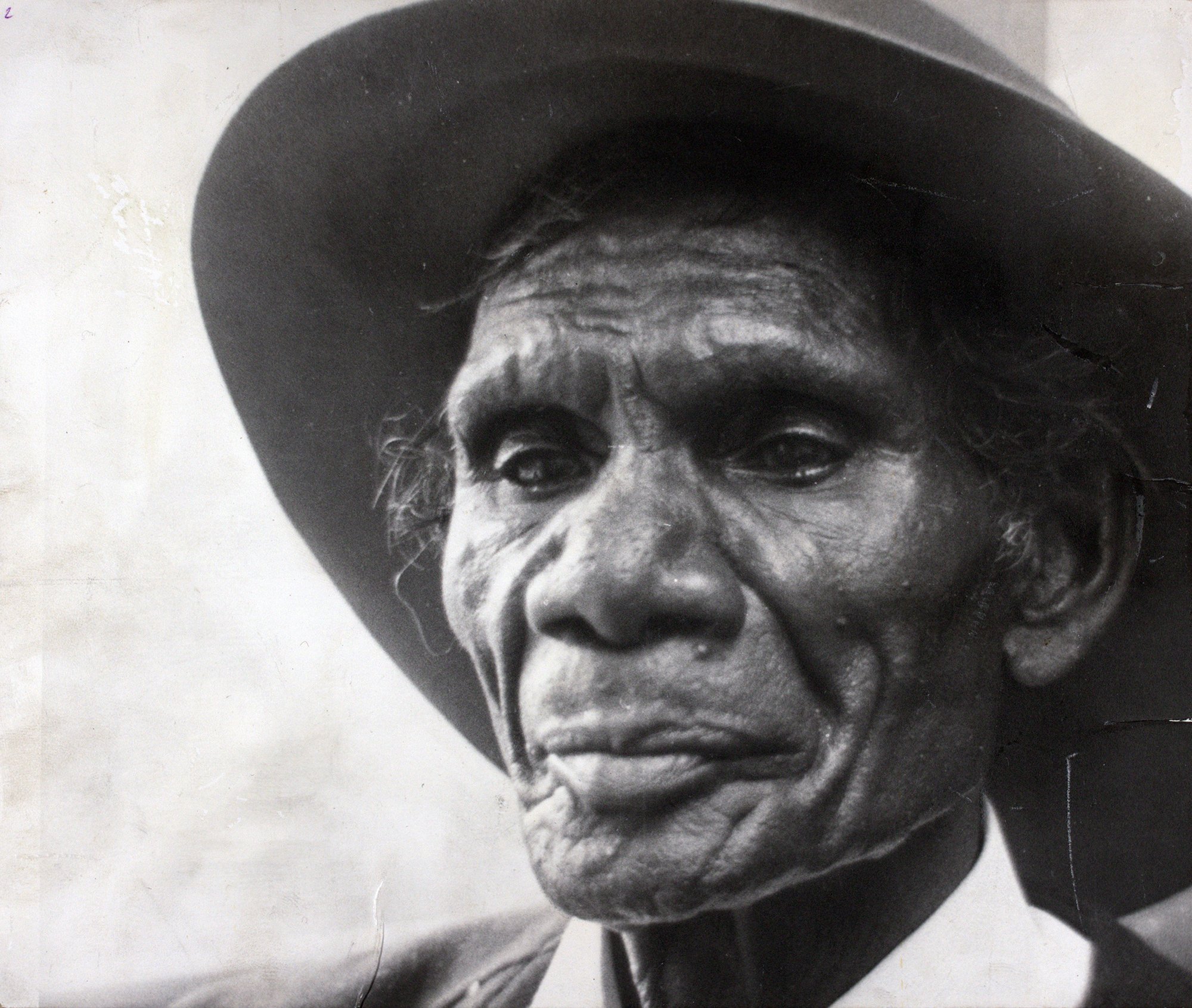

DAVID YIRAWALA

BIOGRAPHY

Born c1894 in his home country of Marugulidban in Western Arnhem Land, Yirawala’s boyhood was spent traveling over the land and learning his father’s sacred designs, songs and stories. His initiation was a long journey, culminating only when at 45 years of age he was endowed with the final secrets. He became a great ritual leader, with knowledge over all the secular and sacred ceremonial content of Kunwinjku iconography. He lived with his first wife at Oenpelli where fathered two children and after her death, the three sons and a daughter by his two promised wives. In the late 1950s the family moved to Croker Island (Minjilang), where a number of artists had collected due to the comparative artistic freedom of the Methodist mission in comparison to the one operating at Oenpelli. However the extent of this freedom is arguable as Yirawala was apparently unaware that the paintings he created over a nine-year period had been sold through the mission until an encounter with collector Sandra Le Brun Holmes in 1964. On telling him the truth Yirawala apparently confided, “All my law. Dreaming story big mob I make, nine year. I bin lose him whole lot, Marain business, Lorrgon, Ubar, magic, all finish. My eye little bit no good now,” (cited in Holmes 1992: 15).

Though devastated by the news, a partnership began between Holmes and Yirawala that marked a turning point in his career as an artist. While organising the filming of Return to the Dreaming in 1971, she arranged for an exhibition of his work to tour southern cities to which Yirawala later traveled and spoke. Artistically the partnership marked a new beginning also. His early work had been preoccupied with Mimih and sorcery stories depicted characteristically in white outlines, similar to the rock art of the region. By contrast, the works that date from the show that was staged in 1970 and onward feature important aspects of the Ngalod, Mardayin, Lorrkkon and Ubar ceremonies. The surfaces of his barks became elaborate and in-filled with intricate cross-hatching within x-ray style figurative forms. Many of the cross-hatched designs (rarrk) were derived from the clan markings formerly restricted to painted bodies during ceremony. Yirawala pioneered these new developments in Western Arnhem Land art at the time, thereby shaping the direction Kunwinjku bark painting would follow stylistically thereafter. He did so, not only through his introduction of rarrk designs, but also in his experimentation in varying the monochrome base colour of the bark. The delek (white) underlay of Luma Luma and Wind Mimi 1971 (illustrated) serves to heighten the elegance of the rarrk designs on the figures. The effect was to highlight the physicality of the figure as an anatomical vision, yet in doing so imbue the subject with spirituality. In this way the “conjunction of the metaphysical and physical elements, the revelation of the cosmic within the concrete, gave Kunwinjku art its transformational edge,” (Ryan J.1990: 77). This is the power to which Picasso referred when he claimed “ this what I have been trying to achieve all my life,” (cited in Holmes 1992: 1). However, in Yirawala’s world, it was only natural that art and life, the physical and metaphysical, were inextricably entwined.

The deed Yirawala drew up with Sandra Le Brun Holmes gave her first option on his work, the majority of which she managed to keep as an intact collection. In 1989 the National Gallery of Australia acquired the Holmes’ collection of 139 bark paintings, marking the first time in the history of the Aboriginal art movement when a ceremonial cycle could be seen visually in its entirety. In this regard she had kept her bargain with the artist and assisted in leaving us with his most lasting and unique legacy. Yirawala was vitally concerned that Balanda (outsiders) should understand the cultural significance of his work, and in doing so build respect for not only his art, but also the culture to which it was intimately connected. Unfortunately his efforts and wishes in this regard largely failed to have the desired effect in his own lifetime. While he became a rising star, and was made a member of the British Empire for his services to Aboriginal Art in 1971, as well as receiving the International Art Cooperation Award in the same year, his efforts to prevent mining in the Western Arhnem Land region of his birth lay unfulfilled upon his death in 1976.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Holmes, S. le Brun, 1992, Yirawala Painter of the Dreaming, Hodder & Stoughton (Australia) Ltd, Sydney

McLean, Ian. June 2005. ‘Kuninjku modernism: new perspectives on western Arnhem Land art.’ Bowdler, Cath (ed.) Artlink, v.25, no.2: 48-51

Ryan, J., 1990, Spirit in Land, exhib. cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.