DOROTHY ROBINSON NAPANGARDI

BIOGRAPHY

Dorothy Napangardi spent her early childhood living a nomadic life at Mina Mina near Lake Mackay in the Tanami Desert during the late 1950s and early 1960s. She recalled camping at claypans and soakages with her mother, Jeanie Lewis Napururrla, learning to collect the plentiful bush tucker and grinding seeds for damper cooked on hot ashes. This idyllic life came to a close when her family was forcibly relocated to the government settlement at Yuendumu. Dorothy’s father, Paddy Lewis Japanangka greatly regretted the move, particularly for its impact on the traditional education of his children. However his attempt to return to country with his family failed and they remained in the government settlement until Dorothy married. She moved with her husband, an elderly man to whom she had been promised at a young age, to Alice Springs and bore him four daughters and later, after the marriage eventually broke down, gave birth to her youngest child, Annette, by another man. It was here, in Alice Springs in 1987, that she began painting.

Dorothy’s early artistic endeavors were heavily influenced by memories of her childhood. Her subject matter was principally the Bush Plum and Bush Banana, wild fruits that grow in abundance near Mina Mina, changing in colour as they ripen, which she mirrored in her depictions. The paintings, at such an early stage in her career, clearly marked Dorothy as an artist of great talent. Her superb sense of composition created a rhythmic effect as semi-naturalistic depictions were entwined in an altogether geometric formation. In the late 1980s, the government marketing company Aboriginal Arts Australia closed its Alice Springs outlet and its manager Roslyn Premont opened her own, Gallery Gondwana. After meeting Roslyn in 1990, Dorothy began painting exclusively for her gallery and the close personal relationship that developed between the two women lasted up until her tragic death in 2013. The studio environment and financial security that Premont provided enabled Dorothy to experiment freely and develop her artistic repertoire rapidly. As it did, she created works that drew on her innate visual consciousness, developed during those early years spent in the vast unlimited expanses of the desert.

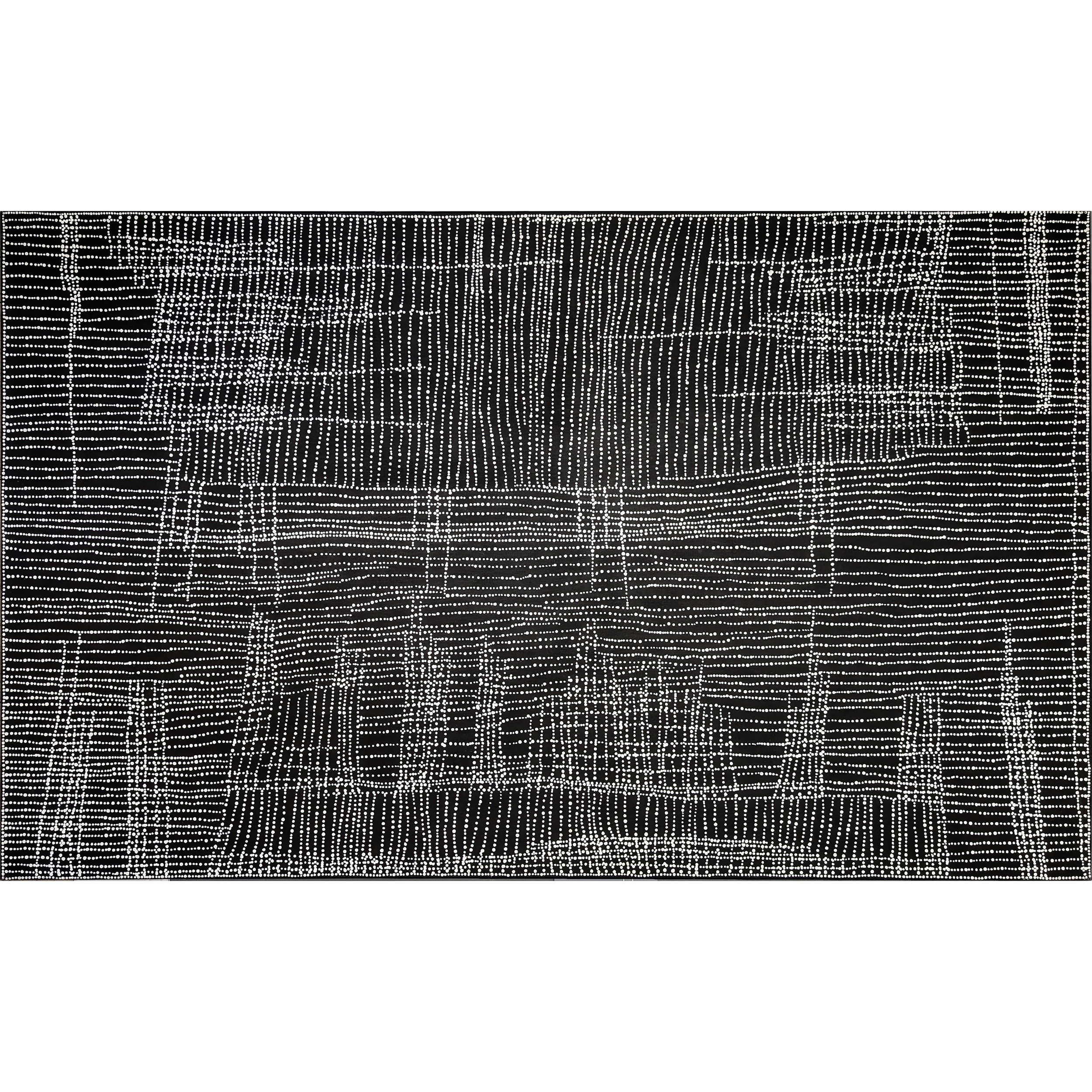

From 1997 onward, Dorothy began producing works which traced the grid-like patterns of the salt encrustations on the Mina Mina clay pans marking a significant artistic shift in her work. Over a three-year period, her paintings became less and less contrived and increasingly spare, all detail pared back to the barest essentials. These new works, in which Dorothy began to explore the Women’s Digging Sticks Dreaming and other stories related to the travels of the Karntakurlangu, compel the spectator’s eye to dance across the painted surface, just as these ancestral women danced in the hundreds across the country during the region’s creation. Dancing digging sticks magically emerged from the ground at Mina Mina, equipping the large band of women for their travels over a vast stretch of country. The tall desert oaks which are found there today symbolise the emergence of the digging sticks that literally rose up out from beneath the ground itself. As these works developed, her extraordinary spatial ability enabled her to create mimetic grids of the salt encrustations across the claypans of Mina Mina. The lines of white dots trace the travels of her female ancestors as they danced their way, in joyous exultation, through the saltpans, spinifex and sandhills, clutching their digging sticks in their outstretched hands. Kathleen Petyarre has been quoted as saying ‘those Walpiri ladies, they’re mad about dancing, they go round and round and round dancing, they’re always dancing’ (cited in Napangardi 2002: 22). Little wonder then, that the surfaces of Dorothy’s canvases become dense rhythms of grids, as she mapped the paths of these dancing women.

In 2001 Dorothy Napangardi was the recipient of the 18th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award and in the following year a solo exhibition of her work was curated for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Through her association with Roslyn Premont and her Gallery Gondwana, Dorothy’s paintings have enjoyed considerable commercial success. Yet despite this close and nurturing relationship, Dorothy continued to occasionally paint for others when moved to do so. These ‘outside‘ paintings are rarely as good as her Gallery Gondwana works. However, there have been exceptions and these have included a number of major canvases painted for Peter Van Groesen and sold through Kimberley Art Gallery in Melbourne. Creating these paintings has in no way undermined her personal integrity. While Dorothy Napangardi’s paintings may be seen as important commodities and major investments, her work can be so beautiful and ethereal, as to border on the sublime.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Napangardi, Dorothy, December 2002, Statement by Dorothy Napangardi, Dancing Up Country: The Art of Dorothy Napangardi, Museum of Contemporary Arts, Sydney.

Nicholls, Christine, Sept -Nov 2003, ‘Thinking big: spatial conception in the art of Dorothy Napangardi.’ Artlink, v.23, no.3: 44-51

Nicholls, Christine, December 2002, ‘Grounded Abstraction: the work of Dorothy Napangardi, ‘ Dancing Up Country: The Art of Dorothy Napangardi, Museum of Contemporary Arts, Sydney.