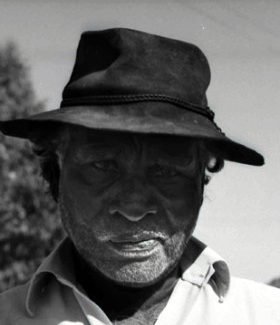

FREDDIE TIMMS

BIOGRAPHY

Freddie Timms began painting in 1986, inspired by the elder artists already painting at Frog Hollow, a small outstation attached to the community at Warmun, Turkey Creek. He was by then, forty-two years old and had lived an eventful life as a young stockman on stations throughout the East Kimberley region. Freddy was born at Police Hole in 1946 and followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a stockman at Lissadell Station. At the age of twenty, he set out to explore and work on other stations. It was during this time that he met and worked alongside Rover Thomas who was to have a lasting influence on him. In 1985, he left Lissadell, to which he had returned after retiring from the physically demanding stockman’s life. He settled at the new community established at Warmun, where he worked as a gardener at the Argyle Mine. He eventually moved out to Frog Hollow with his wife Berylene Mung and their four children, taking a job as an environmental health worker and assuming responsibility for the general maintenance of the small community.

While in the company of elder artists such as Rover Thomas and Hector Jandanay, who were already painting and achieving notoriety at this time, Timms requested art materials from Joel Smoker, the first art coordinator at Waringarri Arts in Kununurra. Smoker visited the community on a regular basis and recognized Freddy’s potential in his first distinctive canvasses and confident grasp of the medium.In a career that spanned more than 20 years, Freddy Timms has become known for aerial map-like visions of country that are less concerned with ancestral associations as with tracing the responses and refuges of the Gidja people as they encountered the ruthlessness and brutality of colonisation. However, his political nature is characterized by more intimate interpretations of the experience rather than overtly political statements.

His first exhibition held at Deutscher Gertrude Street Gallery in Melbourne in 1989 was received with critical acclaim and included a superb masterpiece, Mandangala, North Turkey Creek 1990. In what appeared as a new and beautiful sense of irregular geometry, soft yet boldly defined blocks of colour depicted the area of Glen Hill and the Argyle Diamond Mine to the north of Turkey Creek. The fact that it now lay beneath water, having been flooded by the damming of the Ord River, made the work all the more poignant. There had been no consultation with the traditional Gidja owners. The places where he and his countrymen used to walk and camp, along with all its ancestral burial grounds and sacred places, were simply buried beneath the rising waters.

This underlying political dimension has remained implicit in Freddy Timm’s work throughout a career which has been punctuated by a number of politically explicit works. Another work, Whitefella-Blackfella, acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, overtly states the position of Aboriginal people in Australian society, placing ‘whitefella’ figures at the top, beneath which are painted Chinamen, then African and then finally ‘blackfella right down at the bottom’.

By the mid 1990’s Freddy had become a seasoned exhibitor having traveled to Melbourne once more to accompany and paint with Rover Thomas. He painted a large body of works for Kimberley Art Gallery through its association with the Warmun Community, including two works which currently hold the artist’s highest and third highest prices at auction. Both employ a broader, more colourful palette than the natural earth pigments widely adopted by other East Kimberley artists. This development in his work was widely perceived as a move away from traditional practice and was attributed, at the time, to the influence of Frank Watters, to whom the artist had been introduced by his mutual friend, Tony Oliver. Watters was widely reported as being concerned that Aboriginal artist’s be treated on equal terms as non-aboriginal artists and set about steadily building the value of his works as well as his public profile. His solo exhibition with Watter’s Gallery in 1999 explored the history of an Indigenous bushranger named Major who was shot by police in 1908, after killing whites at Blackfeller Creek. Major holds a strong place in Gidja history, much like Ned Kelly, but remains an ambiguous hero, as his knowledge of the bush reputedly led white men to Gidja camps leading to genocide. Timm’s depiction of Major was influenced by his visit to an exhibition of Sydney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series, evident in the squarish shape he gave to Major’s head. Timms eventually left Frank Watters and after a moderately successful show with Goold Gallery, left Sydney for Crocodile Hole to establish, with Oliver’s help, the Jirrawun Aboriginal Art Corporation. Having firmly established his reputation in the wider art world he produced works of consistently high quality since that time. Although he has yet to achieve a similar level of acclaim to that of the founders of the East Kimberley movement, Freddy Timms is foremost amongst those artists of the second generation. His was a unique Gidja perspective on the history of white interaction with his people. It is hard to think of another who expressed more poignantly through their art the sense of longing and the abiding loss that comes from the separation from the land that embodies one’s spiritual home.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Kofod, Francis, ‘Freddie Timms,’ Jirrawan Aborginal Artists Corporation

McDonald, John, 18 July 1998, Sydney Morning Herald: Interviewer and Author: Francis Kofod.

Ryan, J., 1993, Images of Power, Aboriginal Art of the Kimberley, exhib, cat., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne