JOHNNY WARANGKULA TJUPURRULA

BIOGRAPHY

Born at Mintjilpirri, northwest of the Kangaroo Dreaming site of Ilpili soakage Johnny Warangkula recalled his first contact with ‘white fellas’ at just 12 years of age as a frightening experience. Within three years, his family moved into Hermannsburg mission where Johnny went through initiation. After working on roads and airstrips at Hermannsburg and Haasts Bluff, and time spent at Mount Leibig, Yuendumu and Mount Wedge during the 1950s, he moved into Papunya with his first wife, shortly after its establishment. At the time of Geoff Bardon’s arrival in 1971, he was serving on the Papunya Council alongside Mick Namarari.

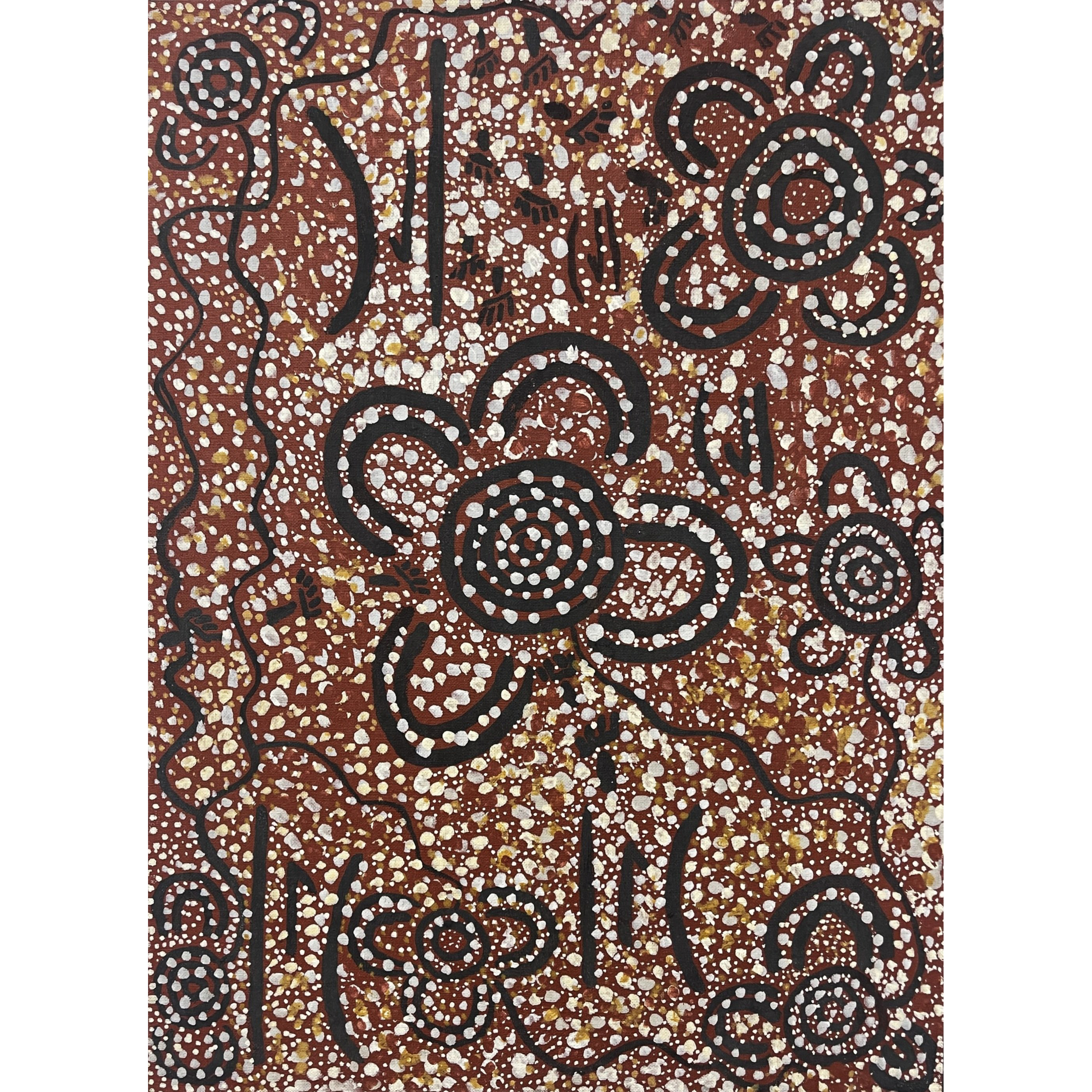

Johnny Warangkula was quick to express interest in painting and rapidly developed a distinctive style characterized by layering and over-dotting, which Geoff Bardon often referred to as ‘tremulous illusion’ (Isaacs 2001: 71).

From the outset of his career as a painter, he intuitively transformed traditional desert ceremonial ground designs into inventive paintings on board and canvas conveying the myths and journeys associated with the sacred waterhole at Ilpilli, the surrounding limestone soaks, its inhabitants and the metaphysics of this country’s creation. Bardon described their friendship, at this time, as ‘close’ and Warangkula as a happy, expressive man who was pleased to discuss his work and explain its meanings and symbols. Bardon was just the first of many to note that Tjupurrula expressed a personal visual style that radiated power from the tightly composed and intensely vibrant surfaces of his paintings.

While dots were traditionally used as decoration and outline in desert art, by the mid-1970s, they were becoming the unmistakable trademark of contemporary desert painting. By 1978 large canvases were being produced by Clifford Possum, Tim Leura, Johnny Warangkula and a number of other Papunya men and Johnny’s Tingari men at Tjikarri was purchased for the Araluen Art Collection after being a finalist in the Alice Art Prize. Warangkula’s success with this, and other works of the period, was in large part due to the energetic effects he achieved in his design motifs while portraying the land as a living force. Dotting was also importantly used to disguise secret images and teachings that were only to be deciphered by the initiated. They became a thin veil, beguiling viewers toward the surface while alluding, even alluring them, to hidden depths.

Warangkula was amongst the most inventive of the early Papunya artists. His 'calligraphic line and smearing brushwork' (Bardon in Isaacs 2001: 71) gave a relative solidity to the features of the land or traced the movements of a journey, picking up on the rhythmic recall of a mythic narrative. Bands of hatching or parallel lines provided visual texture, often interspersed with animal tracks or symbolic figures woven into tightly synchronized compositions that still resound with freshness and surprising spontaneity. Choosing to keep within the hues of traditional earth-based ochres, he achieved in his early paintings a startlingly powerful statement of the earth, his country and the life within it.

During his first 15 years as a painter Warangkula had been foremost among those who had fundamentally shaped the Papunya art movement. However by the mid-1980s, his eyesight began to fail, and his painting became infrequent. By the end of the 1990s, Warangkula was old and infirm. For a time he produced art boards for just $50 each, selling them on the streets of Alice Springs or occasionally painting for Warumpi Arts established by the Papunya Community Council in competition with Papunya Tula. Yet, in what may come as a surprise to those who didn’t know him, after the sale of his 1972 at auction for $206,000 in 1997 and its resale for double the world record price for Aboriginal art in 2000, Warangkula was utterly unperturbed by the publicity and inferences in the media that he should recoup at least some of the financial benefit. At the time he lived mostly in Papunya with his second wife Gladys Napanangka with whom he had two sons and four daughters. After this astounding record sale, he began the first of hundreds of raw expressionistic paintings for local and overseas dealers keen to have anything at all by ‘name’ artists. All but a handful of these late paintings have been shunned by the secondary market which has considered them crude and unworthy of his earlier works.

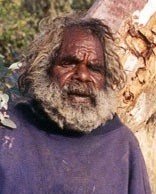

Apart from the patchy work post-2000, the finest of Johnny Waralgkula’s works continue to inspire. Over his thirty-year career, he was a distinctive figure, always wearing his stockman’s hat and charming his visitors with his enigmatic but sincere personality. He was oblivious to the attractions of life beyond the power and responsibilities of his Dreamings. Yet his best paintings not only reverberate with the power of ancient knowledge and forms, but they continue to captivate Western audiences through their uncanny access to our modern sensibility.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Bardon, Geoffrey, 1991. Papunya Tula; Art of the Western Desert, Penguin Books.

Bardon, Geoffrey. 2004. Papunya Tula; A Place Made After the Story, Penguin Books, Victoria.

Isaacs, Jennifer, ‘Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula c.1925-2001’, Art in Australia, v.31 No.1, 2001, 70-71.

McCulloch, Susan. 1999. ‘Central and Western Desert’, Contemporary Aboriginal Art, Allen and Unwin.

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008