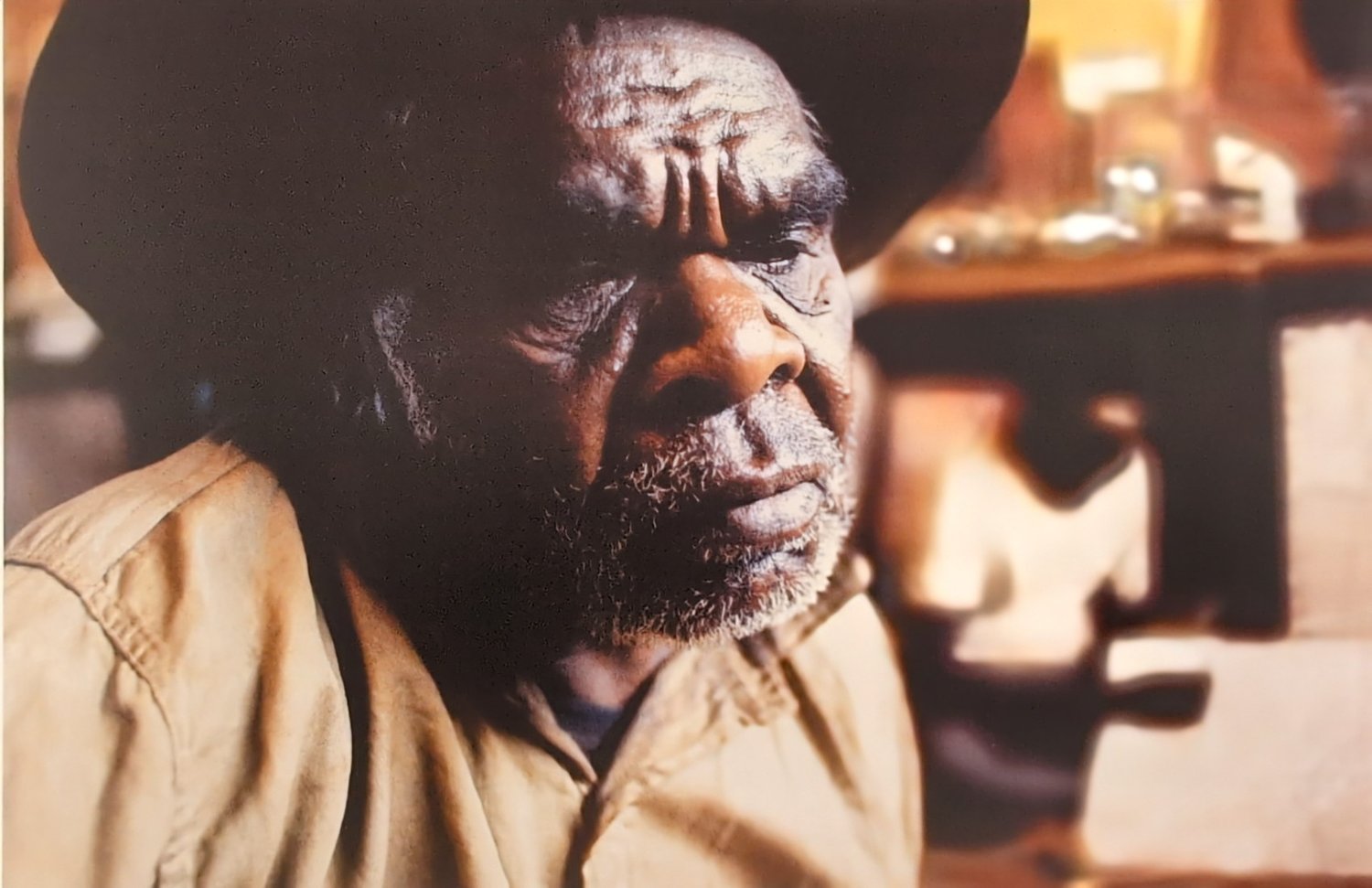

OLD WALTER TJAMPITJINPA

BIOGRAPHY

Walter Tjampitjinpa was already a pensioner at the time Geoff Bardon first visited the Papunya settlement in 1971. He was known to have visited Hermannsburg as early as 1923 in the company of a large group of men and young boys on an exploratory visit from Pintupi country. He was one of the first of the Pintupi people to be re-settled at Papunya and respected as an elder statesman of the community. He spoke little English but nevertheless, was always kind and helpful to Bardon who developed a deep affection for this tall and silent man. Once the Papunya School had shown some support for the men’s painting group and the possibility of earning extra income had been demonstrated by some early art sales in Alice Springs, Old Walter applied himself diligently and with immense concentration to developing his art practice. He had a strong sense of design that enabled him to sidestep controversial sacred material while still conveying the sense of a deeply felt connection to country. Bardon recalls that in all the time he knew Walter he never once managed to raise a smile on that old man’s ‘inscrutable’ face. The comment reflects perhaps the underlying sadness that all of the Pintupi people carried as they attempted to forge a new life, exiled as they were from their traditional life and homelands by the government’s policy of forced assimilation. (Bardon, 2004,p.74)

Old Walter was a senior custodian of Water Dreamings that run through Kalipinypa and most of his paintings were connected with water and the celebration of its life giving force. He was particularly knowledgeable in regard to local Dreaming sites and it was he who was consulted for permission to use the traditional Honey Ant designs for the school mural that was to become such a potent landmark for the fledging painting movement. Old Walter’s restricted palette of traditional ochre colours gave a cohesive regularity to his compositions, which displayed the distinctive Pintupi leaning towards symmetrical structure. He was amongst the first to use the ‘U’ sign for humans, concentric circles for rockholes and wavy lines for water flow, in endless variations and renditions of story. It was these archetypal symbols that first became clear to Bardon as a cultural iconography. They hold a physicality that is never fixed but reflects a constant reading of impressions upon the surface of the land. They tell of “a responsiveness in the earth”(Bardon, 2004,p.45) that prefigures the sacred meanings given to these desert dwellers by their country, signs that were often crucial to their survival in a harsh terrain. It is this interactivity between earth and humans, Bardon felt, that once provided their raison d’etre, and was now revisited through their imagination and memory. Old Water indicated to Bardon that for him the word ‘finished’ was an imposed concept when applied to a work of art. The word is used by Aboriginal people to speak of something ending or even death, where as these Dreaming stories and their related features in the landscape, were eternal. (Bardon, 2004,p.42)

Old Walter’s helped to bring the classic desert iconography to the Australian art world, setting in motion the national and international acclaim that followed. Like others of this generation, his paintings are sometimes remarked upon as the land seen from above, or from an omnipotent viewpoint. Seeing them as ‘Dreaming maps’ gives credence to Bardon’s observation that these artworks elucidate ‘space as an emotional idea’ (Bardon). The human body in this haptic sense is continuous with the earth itself. Humans are ‘of the land’ and feel it’s being in a way that defies the limits of a visual panorama or an intellectual grasp. Bardon was struck by the artist’s need to use song and dance-like gestures to convey to him some understanding of the meaning held within these works; paintings which appear so “severely abstract” (Bardon, 2004,p.49) but are so obviously filled with life and feeling. Old Walter died in 1980. His paintings appear in Australia’s state and national galleries, contributing to the bedrock of our cultural identity.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Bardon, Geoffrey and James, Papunya; A Place Made After the Story, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2004.

Carter, Paul, “The Enigma of a Homeland Place”, in Papunya Tula, Genesis and Genius, edited by Hetti Perkins and Hannah Fink, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000

Johnson, Vivien, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, IAD Press, 2008