TJUMPO TJAPANANGKA

BIOGRAPHY

At the time of his death in 2007, Tjumpo Tjapanangka was Balgo’s most venerated male artist. Having been born c1930, and settled a long distance from his traditional homeland near Karnapilya in the area west of Lake Mackay (Wilkinkarra) he had become the most highly regarded Law Man in the community.

In its infancy Balgo was geographically isolated and often cut off from outside contact for three months during the rainy season. The community comprised primarily of Kukatja and Ngadi speakers. Tjumpo’s group, the former of the two, came to Balgo in 1948 when the local priest, Father Alphonse, sent people into the bush with supplies of flour, sugar, and tea to attract the remaining nomadic groups to the mission situated at Tjumantora. The settlement moved to its present site at Balgo Hills in 1962, and expanded adding new facilities that attracted visits from Warlpiri and Pintupi speakers from Papunya, Yuendemu and Lajamanu, some of whom stayed (Ryan 1989).

Balgo became a melting pot of different tribes, each with accompanying aesthetic and ritual traditions. However, the community remained relatively harmonious and had a less traumatic experience both internally, and in relations with the outside world, than some of the neighboring settlements, where some people were taken away against their will. This fostered a climate of tolerance that encouraged artistic experimentation and a healthy sense of competition between artists eager to outdo each other and bring something new to the creative process. Each artist was ‘ fiercely proud of his or her individual artistic characteristics. They encourage individualism, critisising only when expression is not factual in terms of Aboriginal Law ‘ (Acker cited in Hoy 2000: 48).

Tjumpo who had begun painting in 1986 with the establishment of Warlayirti Artists, embraced innovation from the outset. While his earliest paintings were rendered in the customary autumnal colours characteristic of Kukatja work between 1987-1989 he developed a fluidity of line that initially traced, quite literally, the creek-beds that link the claypans and prominent features of his inaccessible custodial landscape. However his works of this period were just a precursor to the looser brushwork of paintings that followed, such as Wilkinba Near Lake Mackay 1993 depicting the serpent Miliggi. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s he lived at Yaga Yaga, about 150 kilometers south of Balgo Hills toward his country near Lake MacKay. At this time, when I first met him, he was considered the last of the real bushmen and was the most highly regarded artifact maker in the region. He did not move back in to the Balgo Hills community until the Yaga Yaga community was abandoned around 1996.

By 2000 Tjumpo’s artistic experimentation culminated in works such as his masterpiece Kukurpungku 2000. The haptic quality of the work’s execution evokes a sensation of images drawn in the sand with one’s fingers. It reminds us of the relative infancy of acrylic painting in comparison with the ancient practice of sand drawing. Tjumpo’s manner is heavily influenced by this and other earlier traditions, even his tendency towards minimalism is informed by the Kukutja’s iconic preoccupation with the marks or traces left on the land, rather than representing the motif’s themselves. In opting to employ simpler forms to depict the numinous landscape, Tjumpo’s influence spread to other artists and has come to epitomize the transformation that has run through Balgo art since the mid 1990’s. His own works were characterised by subdued linear patterns rendered in cream and yellow with a sparse application of vital elements in red, adding a vibrancy that enabled him to hint at the elemental forces within his depictions of his sacred country. This minimalism, often restricting Tjumpo’s iconography solely to undulating lines, is reminiscent of the Pintupi creative approach. Though Tjumpo’s work, like that of other Kukatja artists, is distinctly less formal than that of the Pintupi, this aesthetic overlap is nevertheless significant. During his career Tjumpo made occasional visits to Kiwirrkura to stay with his countrymen and, on visits such as those in 1999 and 2004, he painted for Papunya Tula artists.

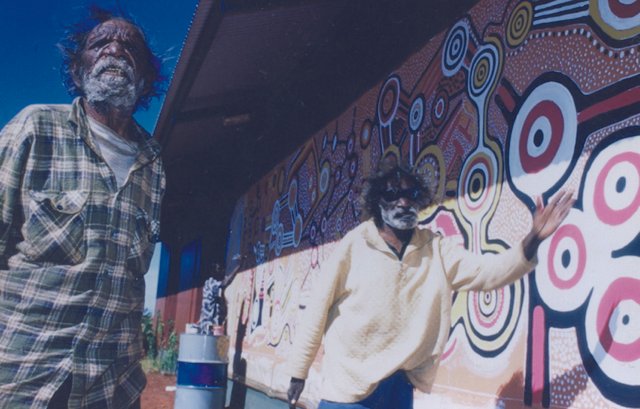

During his final years Tjumpo painted a number of works on a scale that enabled him to achieve that sense of grandeur seen in the large-scale works of a number of his Pintupi contemporaries. It is indeed a pity that artist’s of his ability and stature have not been given greater opportunities to work in large scale as there is no doubt that he was capable of painting great masterpieces.

In both his art and his personal demeanour Tjumpo Tjapanangka affected an infectiously vivacious and animated style. It is this energy and confidence that he employed to build the resonating planes, that characterized his finest works and brought such critical acclaim. His wife Ningie Nangala shared his preference for softer colours, and to some extent this aesthetic can be seen in the more recent paintings created by his stepdaughter, Elizabeth Gordon, to whom he passed on a number of his Dreamings.

© Adrian Newstead

References

Fish, P, 6 August 2005, ‘Aboriginal Work Pushes Magic $1m,’ Sydney Morning Herald, Available Online

Healy, Jacqueline, July 2004, ‘The day the art world came to Balgo: Art Monthly Australia, no.171: 34-36

Hoy, Anthony, 18 Apr 2000, ‘Desert vision,’ Bulletin (Sydney): (46)-48

Ryan, J,1989, Mythscapes Aboriginal Art of the Desert from the National Gallery of Victoria, exhib. Cat, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne